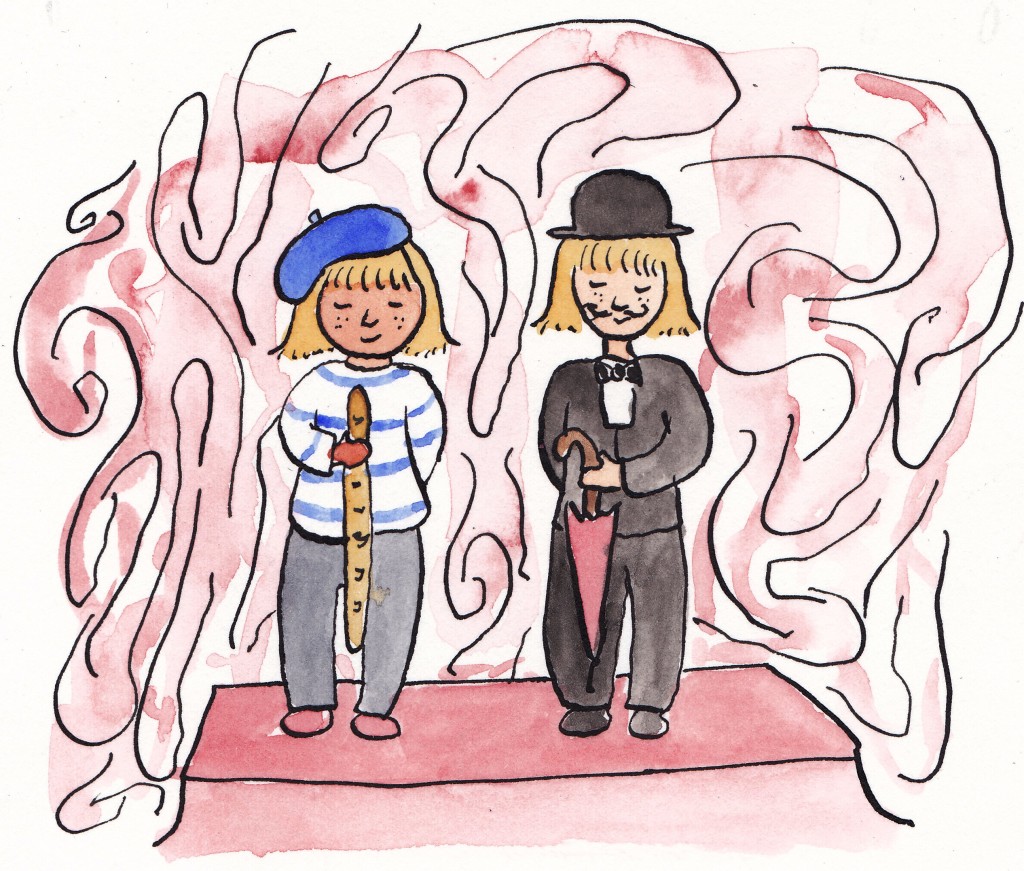

In the part of my brain devoted to languages, French and English dwell in the Chamber of Uncontested Rulers.

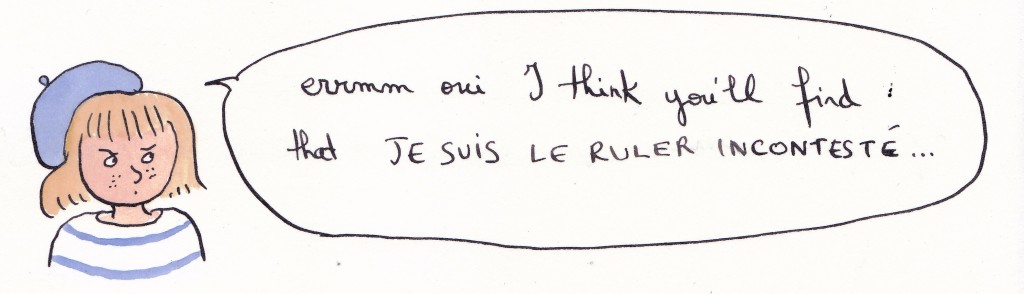

Well, technically French should be the only uncontested ruler, since it’s my native language…

Well, technically French should be the only uncontested ruler, since it’s my native language…

… but my native “academic tongue” is English, and though I don’t write perfectly in English, writing academically in French is actually much more difficult for me – the first article I wrote in French received the following reviewer’s comment:

… but my native “academic tongue” is English, and though I don’t write perfectly in English, writing academically in French is actually much more difficult for me – the first article I wrote in French received the following reviewer’s comment:

“There are a few problems with the language, due to the fact that the author is clearly not a native French speaker”.

But then my English isn’t super strong when it comes to understanding song lyrics. And I can’t baby-talk very well in English. Anyway, French and English occasionally bicker, but they’re generally pretty reliable, and switching between the two stopped being difficult a long time ago.

In another antechamber of the language bit of my brain, however, dwell another two little linguistic daemons who are not quite so disciplined.

Meet Russian and Spanish.

These days, Spanish is happy and having loads of fun, whereas Russian is, to tell you the truth, annoyed and gloomy (and not just because of national stereotypes).

Russian, you see, has been living for almost a dozen years in the Antechamber of the Languages I Have a Basic Knowledge Of. At the beginning, it was living there with English, but English quickly upgraded to the Antechamber of Languages I’m Good At, before moving to the Chamber of Uncontested Rulers along with French.

Russian was cool with that, because I’d started to learn English two years before, so English had a big head start, and also English is a ridiculously simple language to get pretty good at, compared with Russian.

But after a few years, Russian started to realise it wasn’t progressing towards the Antechamber of Languages I’m Good At. We had an awkward chat:

Russian: What’s going on? You’ve been learning me for years and all you seem to be able to do is hold a basic conversation, carefully avoiding using weird aspects and not bothering too much about declensions.

Me: Well, you’re a difficult language and I don’t really have any time to learn all the crazy aspects and declensions. But one day I’ll pick you up again.

A few years later, we had another awkward conversation.

Russian: Hey, where’s English now? Is it still in the Antechamber of Languages You’re Good At?

Me: Um, well, English has done pretty well for itself and has sort of upgraded to the uncontested rulers chamber. But one day, I’ll work on you, Russian, and you’ll move one antechamber up.

Except I didn’t. Instead, one day, I decided (half on a whim) to pick up Spanish.

Russian: Who the hell is this.

At the beginning, Russian imposed its rule. Once, during a Spanish lesson, the teacher said something to me that I didn’t get, and I automatically replied “Я не понимаю” (“I don’t understand”).

Russian was ecstatic. Best joke ever. That’ll teach her to bring this foreigner into my antechamber, Russian said.

So for a while I would say ‘ia’ instead of ‘yo’ (for ‘I’), ‘da’ instead of ‘sí’, etc. I also kept getting some words mixed up because they sounded vaguely similar; the words ‘vez’ in Spanish and ‘raz’ (раз) (‘a time’) were particularly difficult.

But after some time, it became desperately clear to Russian that Spanish was catching up, and then winning.

Now whenever I try to make up a sentence in Russian, such as ‘I’m reading a book’, this is what happens:

Me: No, no, move aside, Spanish – come on, Russian, I’m asking you!

Russian: Oh, you care about me now, do you? I don’t know where those words are. I’m busy.

Me: come on, make an effort!Russian: How about those words instead?

Me: I don’t need those! I need read and book.

Russian: How about this whole sentence?Me: … No! That doesn’t mean ‘I’m reading a book’, it means ‘Attention, the doors are closing’. It’s a sentence you heard in the St Petersburg metro in 2002. Why did you even bother remembering that sentence?

Russian: *shrugs*

Finally, grumpily, and only if the words are on top of the pile, Russian hands me what I need. (But it doesn’t happen very often. Russian is very sulky.)

Me: OK, so now, how do you conjugate and declense those?

Russian: Sorry, I’m going to bed now.

Sometimes Russian is a bit more active and revivified, for instance if I’ve been exposed to a lot of Russian recently. But then Spanish gets angsty because it thinks I’m leaving it alone, so it slyly barges in at the most unexpected moments, replacing prepositions or innocuous little words with Spanish ones. ‘But’, for instance, which, for reasons unknown, I always want to say as ‘pero’ when I try to speak Russian.

When I do, I hear echoes of Spanish’s gleeful JAJAJAJAJAJJAJAJAJJAJAJA (which is hahaha in Spanish) because it’s such a great joke right.

Though I’m no linguist, my guess is that only in the Chamber of Uncontested Rulers can languages cohabit fairly peacefully. All the other languages are Darwinistically condemned to a ruthless war, finishing each other’s sentences, layering over each other’s words, and being generally mean and petty about who gets used more and why.

It’s quite an exhausting battle. Maybe I’m atypical, but my experience seems to contradict the oft-repeated mantra that you get ‘better at learning languages’ if you already know a few. I haven’t seen much of that kind of politeness in my own cerebral antechambers.Sometimes, it’s true, English and French help me understand Spanish a bit better, but only on a lexical level, because some words are closer to English and some to French. So yeah, poor Russian is very gloomy these days. Well, at least, to cheer itself up, it can still go for a nice little stroll across an even darker part of the linguistic corner: the silent, eerie, scary, Cemetary of Completely Dead Languages.

So yeah, poor Russian is very gloomy these days. Well, at least, to cheer itself up, it can still go for a nice little stroll across an even darker part of the linguistic corner: the silent, eerie, scary, Cemetary of Completely Dead Languages.

RIP, Hours and hours and hours of repeating rosa, rosa, rosam, rosae, rosae, rosa.

RIP, Hours and hours and hours of repeating rosa, rosa, rosam, rosae, rosae, rosa.