“So did you have to change a lot of things in your book before it got published?”

“Oh yes, loads.”

“Because you’d made spelling mistakes and stuff?”

“Well, sure, but there are more in-depth changes than that.”

“WHAT?! Like what? Character names?”

“Erm, sometimes, but not just. Things like deleting secondary characters, changing the main plot, taking out secondary plotlines, etc.”

“Your editor made you do that?!?”

“Yes. They’re editors so they edit.”

“And you didn’t say anything?”

“I said I agreed with most of the changes, since I did, and disagreed with some, and then we discussed those.”

“So basically, there’s like, lots of things that have changed between the manuscript and the final book.”

“Yes.”

“That’s awful.”

The Evil Editor who Edits is a prominent mythical figure in common representations of bookwriting and publishing. S/he barges in with a red pen and a hatred of everything aesthetic and beautiful and corrupts and destroys the pure virgin innocent manuscript of the poor author.

There is one central reason for the Evil Editor who Edits to act this way:

MAKE BOOK MORE COMMERCIAL

and absolutely no other reason, certainly not to rectify plotlines that are holey, characters that are hollow, language that is corny, pacing that is wonky and descriptions that are much too long.

There is no way an Editor could possibly do anything like literary appraisal of a manuscript; Editors are cohorts of agents Smith from the Matrix, therefore all they do is make sure that all books published reinforce the general numbness of the docile population. They are controlling and aggressive towards authors because authors are constantly threatening to produce things that will awaken citizens of the world to their situations as Alkaline batteries for gigantic machines.

Your editor edits? You must be weak-willed and lily-livered.

You “shouldn’t be so easily influenced”, “should put up a fight”, and “shouldn’t take any of this”. It’s like you have no self-respect, no respect for your work, and no respect for your readers if you let the Editor do anything to your text.

Your editor edits? Your manuscript must have been awful.

Clearly your book was such a pile of fresh cow dung that it needed to be entirely rewritten by an army of anonymous pen-pushers (god knows why it was taken in the first place, since I’m not Kim Kardashian).

Editors edit; how dare they?

Well that is their job. Editing means modifying a text to make it better, not just Tipp-Exing over typos. Editors are trained readers (see ‘that is their job’); they can spot exactly not just where a text goes wrong but how it could potentially be improved. They will not rewrite but suggest possible ways for the author to rewrite.

Traditionally published authors are not the sole creators of their work (I think self-published authors shouldn’t be either, but that’s another story). The book is the work of a collective and editors have the difficult job of pricing, timing and supervising that collective. Of course they need to ensure the commercial viability of the work, because the book needs to end up in readers’ hands, because the point of a book is to be read. You also need the book to sell or else you won’t eat, remember.

Most of the time, edits are negotiable. If there’s truly a non-negotiable edit and you really, really can’t see why it should be done, your agent will try to intervene. You’re not alone faced with the Evil Editor who dares to edit your work. And you’d be surprised about how little Bowdlerisation actually takes place even in children’s writing. People at Hodder never asked me to modify the vocabulary in the Sesame books, for instance, even though there had been some concern that it was too complex. I couldn’t joke about sex, that’s for sure, but the books talk about money, drugs, poisoning, animal testing, etc.; themes even I thought were probably not going to be accepted. They were.

Yes of course there is censorship in children’s books – god knows we’ve been trying to sell my French books to the UK but they’re too ‘violent and dark’ – but that selection takes place before the book deal, one should hope. Why would an editor take on a book and then ask for all the central sex, drugs and murder plotlines to be removed?

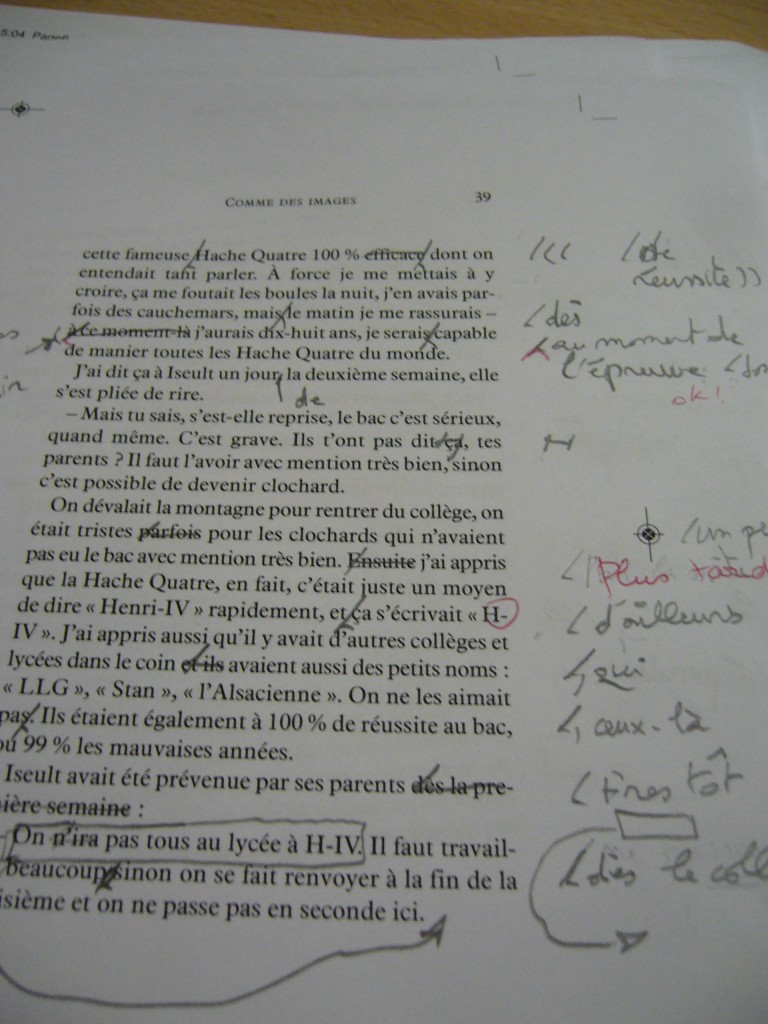

In the best cases, the editor will work tirelessly with you on an extremely ugly first draft and after months (yes, months) of redrafting, two-hour-long phone calls, and dozens of emails, a beautiful swan will emerge from the ugly duckling that Draft 1 was. This is the kind of privileged experience I had with my latest YA in French, Comme des images, which is coming out in February.

First drafts are never publishable as is, and almost never publishable without considerable edits. Yes, even first drafts by established authors. People don’t realise that, because they never see a first draft; all they see is the finished product. Interning in publishing has been such an eye-opener for me: 99% of manuscripts in the ‘slushpile’ truly are terrible; out of the 1% that’s left, almost none of them will actually make it through to publication without several weeks or months of rewrites.

Let me say this again: if you’re still outraged that editors dare to edit, you clearly don’t realise how rubbish most first drafts are.

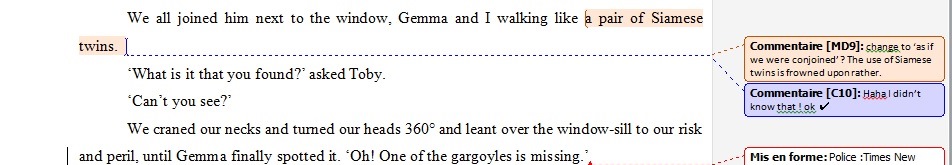

That’s not to say you can’t either get lucky, or get better at writing first drafts that need less editing. Gargoyles Gone AWOL needed much less editing than Sleuth on Skates, and Scam on the Cam even less than Gargoyles. Does it mean I’m getting ‘better’ at writing Sesame books? Well, in a way – in the sense that I’m getting better at anticipating my editor’s issues with the books. If you know an editor well you can preempt their queries, and immediately delete that secondary character you know they’ll say you don’t need.

There’s only one case so far in my writerly ‘career’ (blah) when I was very lucky and got away with the most minor edits, and that was for my YA novel La pouilleuse, which came out last year. It was almost unchanged by my then-editor Emmanuelle. But when I was chatting to my new editor, Tibo, from the same publishing house, he said to me he would have asked me to rewrite quite a lot of the ending if he’d been my editor on that book.

Would it have been a worse or better book? Neither. Both cases, I think, would have worked perfectly. It would have been a different book; my book and Tibo’s, as opposed to my book and Emmanuelle’s. There’s no book without an editor, and the editor’s vision is an integral part of the book.

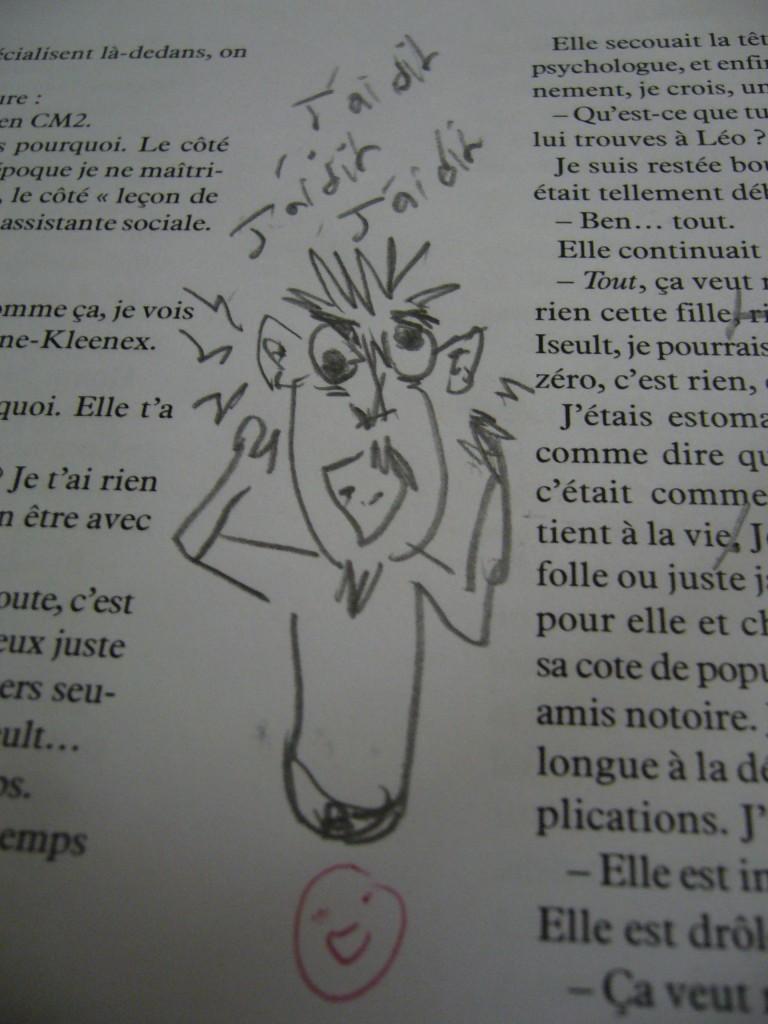

(As well as, sometimes, his marginalia:)

Yes, I am eclipsing in this blog post the numerous problems one can still run into with some editors. It’s because this is a blog post In Defense Of. I know that not all editors are sweet unicorn fowls with manes of caramel fudge. And yes, there are some edits on older books I regret doing and certainly wouldn’t do today. But all of the above remarks are valid in the case of a professional, mutually respectful relationship between a reasonable editor and reasonable author who are both hoping to get a good book out of the ‘evil’ edits.