In the past few months, I’ve done little else than writing book proposals, i.e. being in the hellish no-man’s-land of half-written books and super-polished synopses.

What are book proposals for?

For books following the First One. Even if your publisher has an ‘option’ on your next book (or series), that next book will likely need to be outlined to them before they give you the money and the deadline.

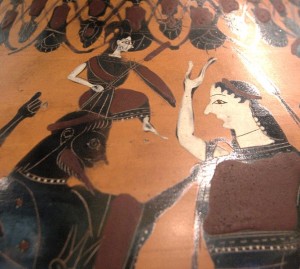

So, in short, the first book (most often) got bought in glorious, fully-armed completeness, like Athena springing out of Zeus’s skull. However, the second must woo the Editor and the Acquisitions team half-finished, half-naked – stripped down to its synopsis and a few chapters.

Book proposals are evidently a ‘good’ thing: if you’re at this stage, it means you’ve got a publisher who likes you and wants to see more of your work. But god, are they a pain to write. Book-writing eroticism degree zero, my friend; degree zero.

The first book was similar to your stumbling in your everyday clothes with graceful naturalness into a roomful of people, and one of them falls in love with your little quirks and endearing youness. A book proposal, meanwhile, is like a long-planned date with a man whose head you’d quite like to see on your pillow (with the rest of the body still attached). You’ve spent the past few weeks checking that you’ve got absolutely everything right to achieve the desired outcome. You’re wearing your hair the way he likes it and have revised all the topics he talks about on Twitter, while making sure you retain some of the aforementioned graceful naturalness.

The sexist undertones of the above paragraph are not fortuitous; there is, in book-proposal-writing, something ineffably demeaning and unnatural, something that kills the uncertainty. Like dressing up in a certain way to cajole someone into liking you, it may give you an impression of control, but definitely not one of power.

What should a book or series proposal contain?

Personally, I write a few chapters; how many? As few as will give the Editor a good sense of the tone, characterisation, and appeal of the book. I write a character list, with short descriptions. A general plot summary. A rough evaluation of the genre(s) that the story belongs to, and the age range. And then a very detailed synopsis.

The synopsis isn’t the worst part for me. I always write synopses for books I’m working on – not always chapter-by-chapter, but I don’t mind doing that. I’m a plotter, obsessively structured. But I can guess how horrible those must be for the many writers who are ‘seat-of-the-pantsers’ – i.e., who don’t know where the story is going before they write it. It must be like asking an explorer to chart a territory they haven’t been to yet.

The writing sample is not hugely fun to write. First, there’s this dull feeling that you can’t get too attached to the story because you might never get to write the rest. This is a strange phenomenon, because when you start something which you’re entirely free to finish, you often lose interest in the story and fail to finish it. But it’s all due to your laziness and/or disenchantment with the idea. Whereas the prospect of someone else effectively preventing you from writing the rest makes you extraordinarily keen to finish the book now.

Why am I saying ‘effectively preventing you’? Well, of course, if your Editor rejects your proposal, it can still be offered to other publishers, though that could cause diplomatic drama which your agent might not want to get into. But if they all reject the proposal, then evidently you’ll never write the book, no matter how much you ‘believe in it’. You won’t waste time in finishing a book no one will want.

Secondly, the sample is dull to write because you know exactly what it has to do: give a feel of the whole story, explain who’s who, set the tone, convince the reader that this will be the best story ever, etc.

Once again, that’s something you’d do anyway in the first few chapters – and yet, when you know you have to do it, you suddenly resent the very concept of an exposition scene, and all you want is to begin with a story-within-a-story, a postmodernist mise en abyme, crazy prologues: in short, everything you really shouldn’t do.

Does it sound like I have a problem with authority? Yeah maybe.

Don’t get me wrong, writing book proposals is a very useful skill to master. It teaches you to think more commercially than you would; it turns you into a judge of your own project in its entirety, not just of the emotionally-charged finished story. It also makes the writing process much more secure: once you’ve got the contract, all is well. A deadline and advance are excellent remedies against writer’s block. And you do feel like you are doing something professional, efficient, controlled.

But I have now been working for months on proposals. I have a book proposal that I worked on all August, and I still haven’t shown it to my Editor because my agent (very rightly) wants me to modify it significantly so it’s more likely to be taken on. Then there’s another one I’m working on for yet another project.

The time it takes for rewriting, redrafting, re-synopsising and discussions is enormous, and all that’s before you even have a contract. It also feels artificial: contrary to the first book, when the Editor and agent didn’t know what would happen, and were reading it literally like normal readers, the book proposal gives away the whole plot. This is good, because it allows the Editor to spot potential plot holes before you can dig them, but also bad, because they’ll never have a ‘virgin’ read of the book.

It’s difficult to get excited, I think, about a book you’ve seen in proposal form. Explaining plots (especially the convoluted ones I like) is boring; everything sounds much more complicated in this condensed form than it will be when it’s developed over two hundred pages. And a story is, of course, not reducible to its structure and plot elements.

I don’t have a romantic view of writing, by the way: I’m very much in favour of demystifying book-writing and publishing. This is a job, and book-proposal-writing is part of the job. I don’t have any patience for people who say it’s all about inspiration, emotion and spontaneity; I think we should take time to think about what we’re doing, to structure and nurture our ideas, and to debate them with editors and agents. A book is the work of a collective. Even in self-publishing, there should be no writers who think they can do it all themselves and know better.

But book-proposal-writing, even with the most literary-minded, enthusiastic authors, editors and agents, gives you a weary feeling of über-professionalism; of the perfect polish, watertight smoothness of prophylactics. A prophylactic against crazy deformed, cross-generic, monstrous fiction-babies; as if no mutations could occur once the blueprint has been deemed impeccable.

I’ll be glad, obviously, if and when one of those is finally accepted for sure, and hopefully they will be just as good as if I hadn’t obsessively reworked their first few chapters and synopses before writing the rest. But I won’t forget that their conception involved quite a bit of eugenic tweaking.