I wrote a guest blog post on the London Writers’ Club blog: ‘5 Top Tips for Writing for Children‘. You can read it here!

And if you don’t know the LWC, and you’re a Londoner and a writer, make sure to check it out!

More updates soon

Clem x

I wrote a guest blog post on the London Writers’ Club blog: ‘5 Top Tips for Writing for Children‘. You can read it here!

And if you don’t know the LWC, and you’re a Londoner and a writer, make sure to check it out!

More updates soon

Clem x

Editing my first manuscript in English is an amazingly different experience to editing my books in French. English isn’t my mother tongue: I started learning it, like most French kids, at school, when I was 10 years old. That means I’ll never be truly bilingual. I’m lucky enough zat I don’t have zis kind of Frrench âccent, but native English-speakers can easily tell that I’m ‘from somewhere else’.

Editing my first manuscript in English is an amazingly different experience to editing my books in French. English isn’t my mother tongue: I started learning it, like most French kids, at school, when I was 10 years old. That means I’ll never be truly bilingual. I’m lucky enough zat I don’t have zis kind of Frrench âccent, but native English-speakers can easily tell that I’m ‘from somewhere else’.

When I first arrived in Cambridge at 17 years old, I already wrote fiction in French, but I never thought I’d ever write in English. Those were days when I merrily got ‘pass out’ and ‘pass away’ mixed up (try it: great way to freak out all your friends). But then I started writing essays, reading more widely in English, and eventually felt like trying out writing fiction in English for a change. That’s when I realised that writing in a different language makes you a different person.

English and French couldn’t be more different. French is structured, rigorous, elegant, poised, inflexible – you can build endless sentences, attaching words together with cohorts of that and which and whose and whom. The subtleties of the syntax and conjugation can turn sentences into grandiose, intricately patterned works of linguistic architecture. Many words retain the length, fibrousness and complexity of their Latin ancestors. Writing in French forces you to be a rational, logical, methodical person. All the fun, the beauty and the craziness have to be grafted onto that grid of grammatical rigour.

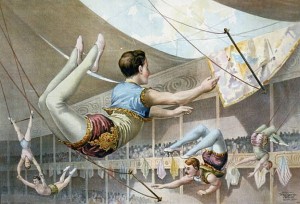

English is the complete opposite. It’s a language of noises, lights, colours, smells, full of wacky alliterations and tiny words, completely anarchic, almost free from conjugation, blissfully unaware of its own grammar. You turn nouns into verbs and adjectives into first names, you let them trip over themselves, you throw commas and hyphens in to help them hold on to each other. It’s a flying trapeze act – unpredictable, colourful, and just choreographed enough that things don’t go crashing into the audience too much. Writing in English forces you to be a zany juggler with an ear for music.

English is the complete opposite. It’s a language of noises, lights, colours, smells, full of wacky alliterations and tiny words, completely anarchic, almost free from conjugation, blissfully unaware of its own grammar. You turn nouns into verbs and adjectives into first names, you let them trip over themselves, you throw commas and hyphens in to help them hold on to each other. It’s a flying trapeze act – unpredictable, colourful, and just choreographed enough that things don’t go crashing into the audience too much. Writing in English forces you to be a zany juggler with an ear for music.

So I’m not just writing different stories, I’m also writing different versions of myself into those stories. And of course I’m more in control when I write in French – but then I find out more when I write in English. For example, I discovered, thanks to my editor, that my English is riddled with Americanisms – but because I probably owe them mostly to one of my best friends who’s American, it makes them a special part of my developing identity as an English speaker. The mistakes and clumsiness of my English all have a story to tell beyond the story I’m trying to tell.

And just as I know there will never be a satisfactory French equivalent for ‘glistening’, and that there will never be a satisfactory English equivalent for ‘démesure’, I know that my ‘I’ will never be quite the same as my ‘je’.

Clem