I thought I’d write a little bit about my PhD thesis, which I defended last year, as I’ve never actually said much about it on this blog or elsewhere. So I’m going to write two blog posts on the matter, for those of you dear readers who might be interested in the relatively unfashionable topic of politically committed children’s literature.

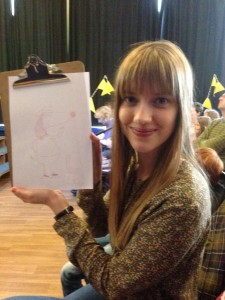

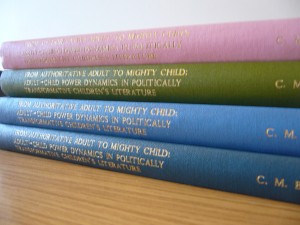

rainbow thesis

In brief: my thesis was principally concerned with children’s literature theory. My starting-point was the currently quite strong theoretical strand of children’s literature which supports the idea that the adult authority, in such texts, is presented as the norm, and/or as more powerful, and the child as other, and/or as less powerful (see list of works at the bottom of this blog post!). My PhD focused on politically committed children’s picturebooks to attempt to nuance this theorisation.

In this first post, a few observations on what politically committed children’s literature looks like today.

Who writes and publishes committed children’s literature these days?

Not a huge amount of people. As I wrote about a couple of weeks ago, France is currently in prey to a pathetic wave of paranoia about committed (feminist/ queer) children’s literature, but in fact most children’s literature internationally remains – in the words of Sartre – ’embarquée’ rather than ‘engagée’, namely ‘carried along’ passively by its values rather than actively ‘committed’. Children’s literature that explicitly either attacks or defends an ideological position is rare.

Plus, some countries are keener than others to publish and to value politically committed books for children. Some, including France, the US, Scandinavia, and some Central and South American countries seem to have a strong tradition of and love for committed children’s literature. They also have a number of small or independent publishers for whom political commitment is an editorial line and commercial strategy. It’s not currently the case in the UK.

Plus, some countries are keener than others to publish and to value politically committed books for children. Some, including France, the US, Scandinavia, and some Central and South American countries seem to have a strong tradition of and love for committed children’s literature. They also have a number of small or independent publishers for whom political commitment is an editorial line and commercial strategy. It’s not currently the case in the UK.

Aren’t politically committed books just politically correct?

No. Of course, ‘political correctness’ doesn’t have a fixed definition, but it is extremely unfair and reductive to claim that politically committed works for children are just saccharine, bohemian-bourgeois texts attempting to show that everyone can be happy together if we would only stop noticing that he’s Black and she’s a lesbian (and all save the Earth by turning off the tap when we brush our teeth).

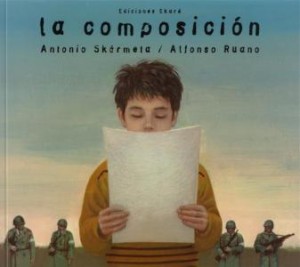

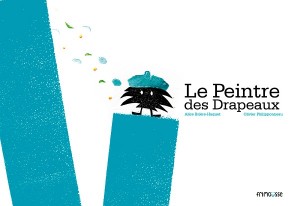

Many politically committed books say very disturbing things about, precisely, our ability to live together peacefully. They don’t say it’s easy, they sometimes doubt it’s possible. This is the case for The Island, by Armin Greder, for instance – a picturebook in which an immigrant is treated atrociously, and then thrown back into the sea, by an insulat community. Or Le Peintre des drapeaux, by Alice Brière-Haquet (The Flag Painter), which ends with the death of the main character who’d been painting flags for war-torn countries…

Going back to Sartre: such books can truly stage the extreme difficulty of living among others; the fact that we’re thrown against one another, with so little explanation, so few reasons to get on, that we’re always at risk of making terrible decisions.

Going back to Sartre: such books can truly stage the extreme difficulty of living among others; the fact that we’re thrown against one another, with so little explanation, so few reasons to get on, that we’re always at risk of making terrible decisions.

But yes, of course, there are also many politically committed books that promote tolerance, friendship, diversity, in naïve and utopian ways. Such books are another facet of the same phenomenon: they try to solve the same anguish. But they do so by giving simple answers rather than asking tricky questions.

And there isn’t one ‘good’ category and one ‘bad’ category, but a spectrum of different books which are all (at least, so I theorised) ideologically ambiguous, even the most ‘simplistic’ ones. It’s this ideological ambiguity that intrigued me.

Does political commitment sell books?

Not to a very wide audience. Politically committed children’s books target very specific groups of people and committed publishers have precise strategies as to which customers they should be approaching. They rely a lot on mediators. They lean on communities of committed reviewers, booksellers, parents and teachers, and on blogs and websites rather than the general media.

Nonetheless, they are overrepresented in major book awards, some of which explicitly value books which lead child readers to think about social and political questions.

Nonetheless, they are overrepresented in major book awards, some of which explicitly value books which lead child readers to think about social and political questions.

Is political commitment the sign of a bad book?

‘Quality’ is a hugely tricky topic, but it’s not justified to state categorically that books which have a ‘message’ are by definition bad books. Publishing houses which focus on such works are in fact generally very keen to focus on aesthetic quality of text and pictures, partly because they know that the books will not sell to a wide audience and that, as a result, the books must seduce mediators and win awards.

Yeah right, but the text and pictures might be beautiful, and the book extremely didactic! No?

Yes, of course. And those texts are clearly prescriptive and pedagogical. They attempt not just to entertain, but also to interpelate the young reader as to the state of the world. This pedagogical function is there by definition.

But before shouting that they’re therefore rubbish since art should be for its own sake, it’s good to think about two things:

1) Supporting politically committed literature isn’t a stupid ideological position. It might sound weird, but it bears repeating. It’s a literary and ideological position which has had quite eminent defenders, from Voltaire to Sartre. Many Nobel Prize winners are ferociously politically committed writers. The opposite trend – ‘art for art’s sake’ – appears in favour these days, at least in ‘adult’ literature. But already in 1963, Roland Barthes was lamenting the ‘exhausting’ alternation of ‘political realism and art for art’s sake, between an ethics of commitment and aesthetic purism’. The seemingly ‘natural’ reaction these days (‘books with a “message” are bad’) is reductive. Political commitment in literature is an amply theorised position which can (and indeed should) be analysed coolly and reasonably (of course I’m saying that because… that’s what I tried to do.)

2) Children’s literature is always-already didactic. Not everyone agrees about this, and many people (especially authors) hate being told that, but for many children’s literature scholars and sociologists of childhood, it’s inescapable. Adults and children are not in an equal relationship with one another. The adult’s ‘mission’ is to socialise the child, whether s/he likes it or not. It’s not a ‘problem’, it’s not a ‘scandal’, it’s not necessarily ‘bad’. Children’s literature is by definition a socialising and acculturating literature, a literature that educates into a society and its values.

It doesn’t necessarily make all adults horrible child-eating monsters

Politically committed children’s literature is a highly prescriptive type of text which reclaims its socialising ‘mission‘ and puts forwards social, political and cultural values in the hope that they will influence the child reader in his or her future life.

Does that mean that politically committed children’s literature manipulates the child reader?

The words ‘manipulation’, ‘indoctrination’, ‘propaganda’, etc. recur among detractors of committed children’s literature. Again, I think it’s a simplistic reaction. ‘Manipulation’ can occur implicitly or explicitly, actively or passively. Feminist critics of (not-committed) children’s books might reproach them with ‘manipulating’ the child reader into associating the presence of one or the other type of genitalia with specific modes of behaviour or types of personality.

Of course, very many politically committed books for children are equally guilty of presenting particular opinions or values as objective and fixed when they are, in fact, debatable and variable.

I’ll stop now, and next time, I’ll share thoughts that are more related to children’s literature theory and the adult-child relationship.

_____________________________________________________________________

Some key works in the area:

On children’s literature theory and the adult-child imbalance

- Gubar, M. (2013). Risky Business: Talking about Children in Children’s Literature Criticism. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 38(4): 450-457.

- Lesnik-Oberstein, K. (1994). Children’s Literature: Criticism and the Fictional Child. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Lesnik-Oberstein, K. (1998). Childhood and Textuality: Culture, History, Literature. In K. Lesnik-Oberstein (Ed.), Children in Culture: Approaches to Childhood (pp.1-28). London: Macmillan.

- Nikolajeva, M. (2009). Theory, post-theory, and aetonormative theory. Neohelicon, 36(1), 13-24.

- Nikolajeva, M. (2010). Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers. New York: Routledge.

- Nodelman, P. (1992). The Other: Orientalism, Colonialism, and Children’s Literature. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 17(1), 29-35.

- Nodelman, P. (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Rose, J. (1984). The Case of Peter Pan: Or the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. London: Macmillan.

On politically committed, or ‘radical’, or ‘subversive’ children’s literature

- Abate, M.A. (2010). Raising Your Kids Right: Children’s Literature and American Political Conservatism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Mickenberg, J. (2006). Learning From the Left: Children’s Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mickenberg, J. & Nel, P. (2008). Tales For Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature. New York: New York University Press.

- Reynolds, K. (2007). Radical Children’s Literature: Future Visions and Aesthetic Transformations in Juvenile Fiction. London: Macmillan.

That is so true. Sometimes when no one else will listen (for instance when I’ve been talking about how much I love quotations that are written in wobbly blurry black writing) I bend over my piece of paper and I whisper things into its tiny little ears.

That is so true. Sometimes when no one else will listen (for instance when I’ve been talking about how much I love quotations that are written in wobbly blurry black writing) I bend over my piece of paper and I whisper things into its tiny little ears. I was saying this the other day to Wilbur (Wilbur is my butler), I was saying Wilbur, you are so lucky to be able to just go on holiday two days a year and forget about all the rest. I just can’t. I can’t. Not. Work. It’s all work work work work and no play ever. It’s hell. And all these thoughts almost always involve thinking of a sepia picture of a typewriter.

I was saying this the other day to Wilbur (Wilbur is my butler), I was saying Wilbur, you are so lucky to be able to just go on holiday two days a year and forget about all the rest. I just can’t. I can’t. Not. Work. It’s all work work work work and no play ever. It’s hell. And all these thoughts almost always involve thinking of a sepia picture of a typewriter.  NO other way to survive. Absolutely NO WAY. Like even if I eat healthy good food all day and take walks and am rich and have no disease, there’s NO WAY NO WAY to survive if I don’t write. I just DIE for goodness’ sake, I DIE every single FLIPPING TIME. I’m so happy someone’s finally voicing this survival impossibility thing.

NO other way to survive. Absolutely NO WAY. Like even if I eat healthy good food all day and take walks and am rich and have no disease, there’s NO WAY NO WAY to survive if I don’t write. I just DIE for goodness’ sake, I DIE every single FLIPPING TIME. I’m so happy someone’s finally voicing this survival impossibility thing. OH GOD don’t you hate it when you’re writing in your dreams and someone removes the pen you’re holding in reality which is the pen you’re writing with in your dreams? It completely ruins everything you’re writing in your dreams and your dream book doesn’t get written. Then you’re late on your dream deadline and your dream editor gets so furious! I had to pay back a whole dream advance like that last time because the boyfriend had removed my pen from my hand (‘It was going to stain your pyjamas’ SURE). Such a shame you don’t ever get a dream pen and all this dream writing is conditional on your holding a real pen THANK YOU UNCONSCIOUS.

OH GOD don’t you hate it when you’re writing in your dreams and someone removes the pen you’re holding in reality which is the pen you’re writing with in your dreams? It completely ruins everything you’re writing in your dreams and your dream book doesn’t get written. Then you’re late on your dream deadline and your dream editor gets so furious! I had to pay back a whole dream advance like that last time because the boyfriend had removed my pen from my hand (‘It was going to stain your pyjamas’ SURE). Such a shame you don’t ever get a dream pen and all this dream writing is conditional on your holding a real pen THANK YOU UNCONSCIOUS. I think he doesn’t mean really bleeding, I think it’s a metaphor of some kind, but it’s so true because when you write it hurts so much it really feels exactly like someone’s cut your veins open and all the blood is gushing out. It really hurts physically like that. It does. But it’s nothing at the same time, nothing. We endure it, we have to. Seriously, it’s nothing. Don’t worry. It’s nothing. Ouch… o the pain.

I think he doesn’t mean really bleeding, I think it’s a metaphor of some kind, but it’s so true because when you write it hurts so much it really feels exactly like someone’s cut your veins open and all the blood is gushing out. It really hurts physically like that. It does. But it’s nothing at the same time, nothing. We endure it, we have to. Seriously, it’s nothing. Don’t worry. It’s nothing. Ouch… o the pain. That really strikes a chord with me. I know people who are not writers and it must be strange not to feel desperate all the time. It’s funny to think that we’re the ones who have this burden, this calling, this thing in us that makes us so desperate… Why us? I hope it stops one day because there’s so much despair, but at the same time I don’t want it to stop because I wouldn’t be a writer anymore… Oh I just don’t know.

That really strikes a chord with me. I know people who are not writers and it must be strange not to feel desperate all the time. It’s funny to think that we’re the ones who have this burden, this calling, this thing in us that makes us so desperate… Why us? I hope it stops one day because there’s so much despair, but at the same time I don’t want it to stop because I wouldn’t be a writer anymore… Oh I just don’t know. I like the definition of courage that’s implied in there, because some people would say that courage is, like, jumping into a house on fire, or facing up to someone who’s a horrible racist and misogynist, or finally breaking up with a partner who emotionally manipulates you, but no one ever, ever mentions the courage that you need in those moments when you have to write in a way that scares you a little.

I like the definition of courage that’s implied in there, because some people would say that courage is, like, jumping into a house on fire, or facing up to someone who’s a horrible racist and misogynist, or finally breaking up with a partner who emotionally manipulates you, but no one ever, ever mentions the courage that you need in those moments when you have to write in a way that scares you a little. YESSS!!! I mean, YESSSS!!! The sheer number of people I meet who will just tell you offhandedly, ‘Writers’ idea notebooks aren’t important to them’. It’s extraordinary, it’s like you can’t have a normal conversation with anyone without them bringing up that topic. And the effort it takes to convince them otherwise! Next time I’ll just give them this picture and they’ll understand with the broken glass and fishnet wire that we mean it.

YESSS!!! I mean, YESSSS!!! The sheer number of people I meet who will just tell you offhandedly, ‘Writers’ idea notebooks aren’t important to them’. It’s extraordinary, it’s like you can’t have a normal conversation with anyone without them bringing up that topic. And the effort it takes to convince them otherwise! Next time I’ll just give them this picture and they’ll understand with the broken glass and fishnet wire that we mean it. I hate those simultaneous yet contradictory delusions. They happen all the time, for instance if I’m tweeting ‘Difficult day with characterisation #amwriting’ and no one retweets or replies, and I think ‘Is that because 1) they don’t care 2) they haven’t seen the tweet 3) they never have this problem with characterisation 4) they’re scared of admitting they have the same problem 5)…’ At least this quote reminds me I’m not alone.

I hate those simultaneous yet contradictory delusions. They happen all the time, for instance if I’m tweeting ‘Difficult day with characterisation #amwriting’ and no one retweets or replies, and I think ‘Is that because 1) they don’t care 2) they haven’t seen the tweet 3) they never have this problem with characterisation 4) they’re scared of admitting they have the same problem 5)…’ At least this quote reminds me I’m not alone. This one is my top number one favourite of all. I couldn’t agree more. Break-ups, deaths, illnesses, genocides, sun death – there are things out there that sound like they could cause agony of a kind or another. But to me, nothing, nothing can ever be equally agonising as the knowledge that I have a story in me that isn’t told. It’s the Platonic idea of agony; everything else is a replica.

This one is my top number one favourite of all. I couldn’t agree more. Break-ups, deaths, illnesses, genocides, sun death – there are things out there that sound like they could cause agony of a kind or another. But to me, nothing, nothing can ever be equally agonising as the knowledge that I have a story in me that isn’t told. It’s the Platonic idea of agony; everything else is a replica.