First published on An Awfully Big Blog Adventure.

Last Wednesday, my latest YA book came out in France :

It’s the culmination of 12 years of observing the British, and gradually sort-of-becoming one myself, a process of transformation not as painful as it sounds. It’s the very first time one of my French books is set in Britain, and, as its almost-500 pages testify, maybe it was long overdue.

Here’s my pitch, elevator-ready : in post-referendum Britain, a canny entrepreneur, 21-year-old Justine Dodgson, sets up a start-up – the eponymous Brexit Romance – to match young Europhilic Brits to generous-minded French people, for the purpose of entering into arranged marriages. Five years later, in theory, the former would gain the nationality of the latter, and thus get back their European citizenship. The only condition, however, is to Not Fall In Love. In practice, this is difficult.

Aside from Justine, the main characters include an innocent and romantic French girl, her grumpy Marxist-Leninist singing teacher, a young lord – and son of the leader of UKIP – and a beautiful British-American lawyer. As you may have guessed, it’s a rom-com of sorts, often verging on screwball comedy, and it’s also, as the title indicates, not too far from social and political satire. But it’s also, eminently, about cultural and linguistic tensions, often endearing, sometimes exasperating, between France and Britain, and French and English.

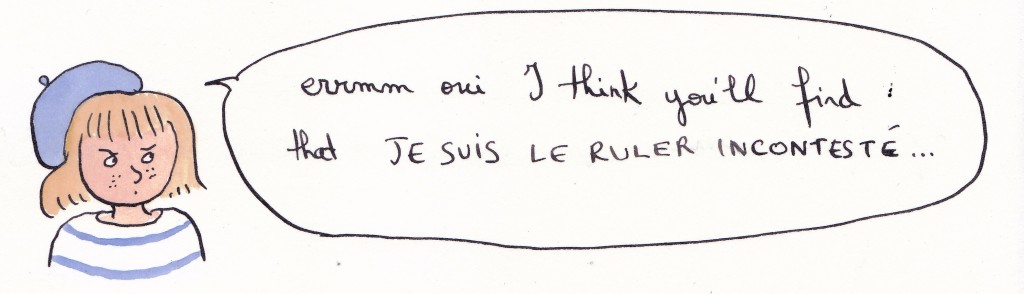

Form matching content, it’s written in a kind of Frenglish, or rather what I’d call ‘literary translationese’. ‘Translationese’ is generally used derogatorily, to refer to sentences that ‘feel translated’ – think, for instance, of Facebook translating your international friends’ statuses. But I mean it here positively, creatively: literary translationese, as I use it in Brexit Romance, is a way of writing in French that deliberately uses lexical calque and syntactic mimicry of English, as if to imitate the feel of a translation. It allows for a lot of fun things, from basic wordplay to painstaking rendering, in French, of the convoluted sentence structures of British politeness – je ne suppose pas que vous soyez libre dans trois semaines ?

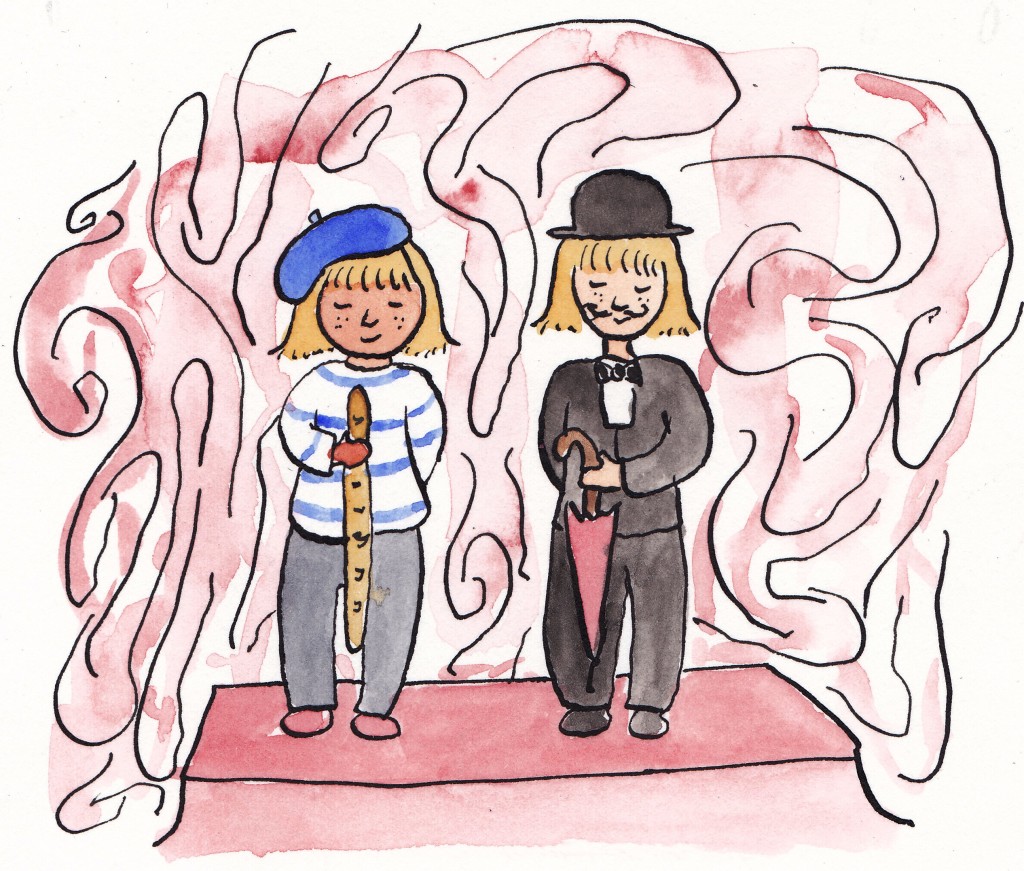

Literary translationese occurs, famously, in Asterix in Britain, where all the ‘Bretons’ in the French version preface every sentence by ‘Je dis’, answer every statement with ‘Plutôt !’ and reinforce their assertions with an ungainly ‘n’est-il pas ?’, all of which baffled and delighted my 10-year-old self.

|

|

available in English translation by A. Bell and D. Hockridge |

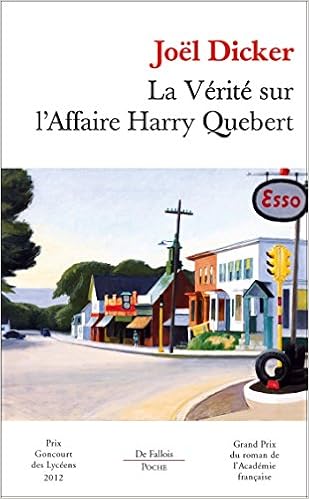

More recently, francophone Swiss writer Joël Dicker wrote The Truth in the Harry Quebert Affair, which reads, in French, ‘like a bad translation’ of an American crime novel – quite in keeping with the story, which is about an American writer writing about a crime involving another American writer (available in English translation by Sam Taylor). Another favourite of mine in the literary translationese category is Marie-Aude Murail’s sprawling teenage novel Miss Charity, a fictionalised biography of a Beatrix Potter figure, which audaciously espouses, in French, the phrases and lexicon of 19th-century British novels and of their classic translations into French.

Literary translationese pushes to its comical and beautiful extremes the daily involuntary instances of translationese that texts all around the world occasionally slip into. It aestheticises Globish, glorifies lazy Englishisms. Few people are more guillotine-worthy, in French, than those who use the verbs ‘réaliser’ or ‘supporter’ to mean ‘become aware of’ and ‘support’ (a team) – but use them in the right literary context, and suddenly the repulsive statement ‘Il supporte l’équipe de France’ can take on a new texture, turning football devotion into some kind of existential burden.

I particularly love literary translationese when it elevates to the rank of the finest surrealistic devices two things which we learn at school to be ultimate crimes against literature : the calque, and the cliché. He stormed out of the kitchen, says the English author who’s completely run out of energy to find non-banal ways of expressing the character’s anger. But nothing cliché in the outrageous French calque il s’oragea de la cuisine, halfway between orage (very much not a verb) and s’arracher (a familiar way of saying ‘to get out of here’). That sentence is intolerable in any literary context that doesn’t firmly invite a reader to delight in its being written in literary translationese. Once it’s there, though, it speaks its own quirky, playful language.

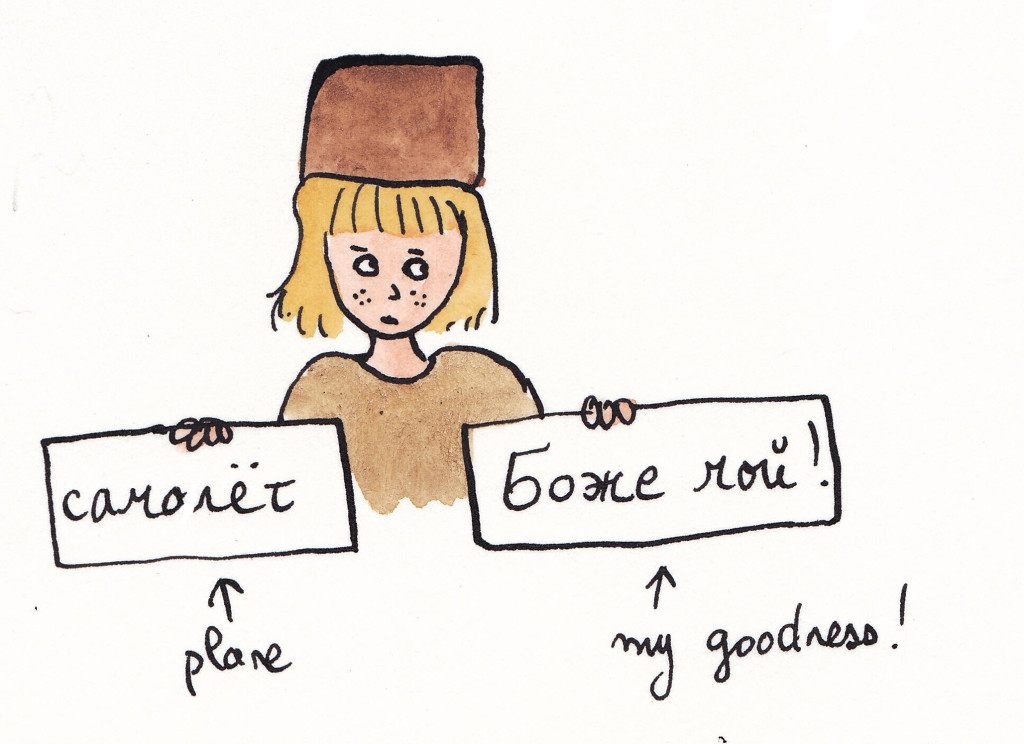

Learning other languages, one dreams sometimes of multilingual adventures in literary translationese ; women who would ‘give light’ to babies, as they do in Spanish, or bold experiments in the acrobatic word orders of declension languages, in languages that aren’t graced with the same toolbox of suffixes. The point of literary translationese, however, is not to turn readers into supersleuths, working out which expressions in which language have been borrowed and exploited. It’s to create a literature that joyfully, weirdly and, sometimes, nonsensically, celebrates the impossibility of maintaining watertight boundaries between literary languages in the first place.

In doing so, it also celebrates, indirectly, translation and its literary influence. The texture of translations has profound consequences on the literature of any country ; translations and their conventions condition our reading, and they also modify our writing.

We catch ourselves writing, in French, a million times per page, ‘Il haussa les épaules’, or ‘Elle cligna des yeux’, because English is a real spendthrift when it comes to telling us about people’s body language – even though French handles much more clumsily those innocuous He shrugged, she blinked. We are contaminated by the inbuilt English precision as to whether someone is currently standing or sitting, and we end up writing ‘elle était debout dans le couloir’, because we’ve read countless translated books where people are ‘debout dans le couloir’, instead of simply ‘dans le couloir’ – because in conventional French we can safely assume, unless otherwise stated, that a person in a corridor probably isn’t sitting, crouching or doing a headstand.

One interesting phenomenon of this ‘contamination’, as far as YA is concerned, has been the rise of the use in popular French YA of the term ‘marmoréen’ to refer to skin. ‘Marmoréen’ is an extremely literary, high-register way of saying ‘marble-like’ (‘marmoreal’ in English), and its incongruous use in contemporary popular YA otherwise written in low to mid register can probably be traced back to Luc Rigoureau’s French translation of Twilight, which used the word repeatedly to refer to Edward’s skin, translating Meyer’s more neutral ‘marble’. The word has become its own meme, and I can’t imagine, as a French YA author, ever using the term ‘marmoréen’ today in any way other than humorously. But with the right crowd – one attuned to precisely those connotations of ‘marmoréen’ in French YA today – that humorous use could be very powerful indeed.

From accidental translationese to literary translationese, the difference can be subtle – it’s about self-reflectiveness, artistic playfulness, and, to an extent, low-key political activism in literary form. It is indeed a political statement of sorts, especially when literary translationese is used with English as its point of reference, to calque English, and thus by definition make its influence visible, and thus makes its domination visible. It calls into question the ‘accidental translationese’ that happens all the time in countries where translations from English are ubiquitous (i.e., most countries), and suspends the transparency of that process for a moment.

I suspect it is exactly the same for other languages that might use literary translationese with French, or other locally hegemonic languages. It’s an act of linguistic love, but also of linguistic teasing, or even linguistic nagging.

Unfortunately, I can’t think of any novels in other languages than French that use literary translationese with English. For a good reason, doubtlessly : those novels don’t get translated into French, because literary translationese is horribly difficult to translate. It’s possible, of course – no such thing as untranslatability ! – but you can sort of understand why publishers are wary of it. And it’s also tricky because literary translationese is a linguistic love affair between two languages, so it would be quite difficult to get the gist of, say, a translation into French of a German novel that mimicks English turns of phrase. It’s the kind of in-joke that doesn’t travel very easily.

Long post, sorry. Let me know in the comments of your favourite instances of literary translationese in English or other languages…