I wanted to take the time to reply to an article published in ‘Intelligent Life’, which a Facebook friend of mine mentioned to me recently.

The article, written by Malika Browne, and theatrically entitled ‘Why there’s no French Harry Potter’, is an extremely uninformed opinion piece, of the ‘as a parent, I…’ type, about the assumed ‘dearth’ of ‘good’ French literature since Astérix, The Little Prince and Babar (which apparently were adult books anyway).

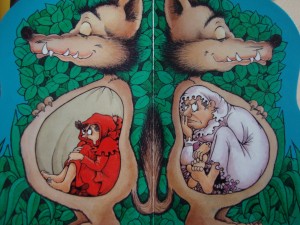

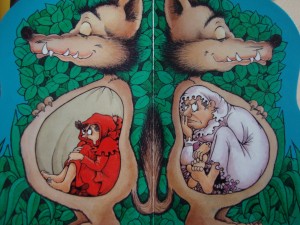

She also deplores ‘a baffling number of books about wolves’. (here, Claude Ponti)

The following response might not be devoid of snark and sourness, but I hope it addresses fairly the points raised by Ms Browne. I recognise that of course my point of view is biased, as both an author of French books and a children’s literature scholar, and since I’m not a parent, there’s clearly some mystical misunderstanding of children in there too. But please bear with me. You may pick and choose the points I’ve addressed, since the whole post is quite long, and I’ve tried to sum up Ms Browne’s arguments so you don’t need to refer back to her article all the time.

At the end of the post you will find a whimsical and subjective selection of what Ms Browne says doesn’t exist, i.e. funny, witty, sweet contemporary children’s books in French.

– As a parent, I…

You know an article is going to be of excellent journalistic standard when it begins with a paragraph explaining that it stems from the journalist’s children not liking something, thereby sending their investigative-minded genitor on a quest for a rational and universal explanation for that dislike.

In this particular case, Ms Browne’s children apparently do not like French (picture)books as much as The Tiger Who Came to Tea. A justification for this dislike has to be found and formulated in absolute terms, omitting to mention the strange correlation with the fact that Mummy doesn’t seem that keen on those books to start with.

The ‘as a parent’ argument (argumentum ad having-successfully-reproducedum) is one of the most hopelessly boring, relentlessly repetitive argument we hear in all conferences and seminars. There might be a thousand and one reasons why Chloe and Lucas don’t like something, but since there’s no way the little cherubs can ever be wrong or influenced by other people, their dislike has to be subsumed by some intrinsic flaw in what they don’t like. This is the narcissistic premise of Ms Browne’s whole article, and it’s a tiresomely predictable one.

– ‘French children’s books seem aimed more at adults than children.’

Oh hello argumentum ad this-is-an-adult-bookum. It perfectly sums up Ms Browne’s whole article, which is scintillatingly anti-intellectual and relentlessly ageist.

She points out that France has some nice classics, like Babar (she finds it ‘patronising’ and ‘colonialist’, though, which are, ironically, two adjectives I’d gladly apply to her own article), The Little Prince, and Astérix. She then asserts categorically that The Little Prince is ‘rendered … opaque by its abstract philosophising’, and that’s the end of the story. This is one of the many occurrences in the article when it is clear that her literary standards are quite low, and/or that she does not believe children to be capable of reading complex texts.

Her ‘argument’ about Astérix is incorrect, absurd and frankly quite insulting:

“Asterix” is different, with its uncharacteristic, word-based wit and self-deprecating Frenchness. But it belongs to the bande dessinée category—a quite different sector, distinctly Francophone and mainly aimed at adults. Its writer, René Goscinny, may have written in French, but he was born to Polish immigrant parents and only moved to France at the age of 25. So perhaps it is the exception that proves the rule.

No, the bande dessinée (comics) category is in no way a ‘different sector’, ‘mainly aimed at adults’. Kids avidly read comics, and of course they avidly read Astérix, but also the Smurfs, Tintin of course, and more contemporary ones like Titeuf. The bande dessinée industry relies greatly on the child part of its audience.

No, Astérix is in no way ‘uncharacteristic’ because of its ‘word-based wit’ and ‘self-deprecating Frenchness’. French children’s literature is full of ‘word-based wit’, if she would take the time to look. Every child of my generation in France has read Le Prince de Motordu, by Pef, which delightfully plays on words that sound the same. The Fantômette series by George Chaulet is full of wordplay and humour. The Little Nicholas series by René Goscinny and Sempé is not only hilarious, but also a decidedly ‘self-deprecating’ look at the middle classes of the 1960s. And nowadays, French children’s literature is more playful than ever with language – cf. the list at the end of this blogpost.

Her final ‘argument’ about Goscinny being Polish (and therefore native French children’s authors can’t be funny) is so despicable that I won’t even deign comment on it.

– ‘When I ask French friends if they agree, they respond in the same puzzled way as when I mention the French practice of no school on Wednesdays, of flunked students retaking the school year or the national fondness for suppositories.’

This sentence, among others, betrays particularly clearly how much the author is speaking from an Anglocentric position (I don’t know, by the way, whether she is French or not; but even in the former case it wouldn’t mean she can’t be anglocentric of course).

To a French person, there is nothing absurd in the idea of ‘flunked students retaking the school year’, because the whole school system is designed to allow for this possibility (students can skip years too). Ms Browne is here relying on a reaction of surprise and/ or mild condescendence, but this statement is only surprising for, guess what, people who aren’t used to this educational system. As for suppositories, you can shove that national stereotype in whichever bodily orifice you prefer. Only small children are administered it, it’s not exactly a daily activity for the over-6.

Anyway, ‘asking (random) French friends’ about contemporary children’s literature is a fairly idiotic thing to do. I don’t ‘ask British friends’ about contemporary British music or about contemporary British cars because there’s 99% chance that they’ll have no idea. And yes, even parents – it’s an amazing fact that becoming a parent doesn’t seem to endow you suddenly with a good knowledge of contemporary children’s literature. It has even been suggested that parents tend to go back to classics they read as a kid, or to pick randomly from what seems to be popular at the moment – incredible, I know.

It’s a rara avis in the land of parenthood who takes the time to read specialist magazines and blogs on children’s literature. And I don’t know who she’s talking to, but if Ms Browne doesn’t actually live in France, the friends she’s asking are likely to be fairly unaware of what’s getting published hic et nunc.

– Getting tense: French books tend to use the ‘difficult’ tense of the passé simple

Ms Browne is bamboozled, apparently, that people writing in a language that has a specific past tense especially designed to tell stories use this tense to tell stories.

It is a fairly difficult tense, don’t get me wrong. But you do have to learn it at some point, so why not earlier rather than later? And at six years old I had no particular problem with it, and later wrote stories using it. It’s depressing to hear, once again, such an anti-intellectual statement: something is difficult, therefore it’s not fun.

However, Ms Browne should be reassured to hear that – to the despair of many – the passé simple is used less and less these days in both adult and children’s literature. One day it will disappear, and Ms Browne’s happy land of absolute simplicity will be born, just right for her literary, linguistic and cultural standards.

– It is difficult to be poetic for children in French.

This is such a ludicrous argument – presented, to be fair, in the form of a rhetorical question – that I actually laughed out loud. But I am stunned that a magazine calling itself ‘intelligent’ okayed this sentence without raising an eyebrow. Ms Browne wonders out loud whether it could be that French, ‘with many words ending in a silent “e”, and a relatively small vocabulary (it is said to contain a fifth as many words as English), is less conducive to rhyme and puns and onomatopoeia’, explaining the ‘lack of fun in the writing’.

It is news to me that silent ‘e’s kill all the fun, but then there is one in my own first name, which could explain my complete lack of humour. As for the ‘relatively small vocabulary’, I will venture to argue that French publishing is much more tolerant of authors using a very big part of that vocabulary, while UK and US publishing tends to be more afraid of big words.

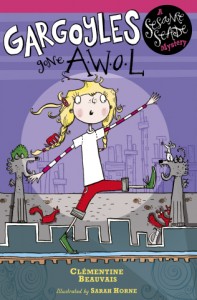

Anyway, I refer Ms Browne to my upcoming picturebook Lettres de mon hélicoptêtre, published by Sarbacane in 2014, which should do exactly the kind of thing she’s looking for in terms of wordplay, alliterations, assonance and rhyme. In the meantime, she is welcome to take a look at the list of picturebooks I have provided at the end of this blog post.

– ‘The British market is richly supplied without needing to import books’

No, that’s absolutely incorrect. The British market HAS DECIDED that it is richly supplied without needing to import books.

It’s not a fact; it’s a commercial decision subsumed by the very dubious sociocultural statement that the UK and the US are able to be culturally autarchic. French publishers, like, in fact, publishers from all non-English-speaking countries, import books in English and books in other languages, because beyond the commercial viability of this model there is also the assumption that children will benefit from encountering books from different cultures, and will be able to.

The hermetism of the UK/US market to books from other countries is something to be deplored and fought against, not something to be celebrated as evidence of awesome creative self-sufficiency on their part. This argument makes me weep.

– French children’s literature is didactic and dark

Absolutely, it is dark. I don’t think we’re on the same wavelength there, Ms Browne and I, so I won’t bother to argue, but when she says that many French books don’t have a happy ending, she seems to see it as a problem, whereas I dance around my living-room with aesthetic joy. But that’s a question of personal taste, and also something that probably gets modified once you have children who might wake up in the night with nightmares and monopolise half of your bed. But yes, French books are darker than UK/US books, I don’t deny it.

But Ms Browne then produces a magnificent argument from authority, using a quotation from an Irish mother based in Paris (note, again, the superb ‘as as parent, I…’), saying that classic children’s book Les Malheurs de Sophie ‘leaves readers with emotional despair’.

Let me resort to an ‘as a reader, I…’ argument. Les Malheurs is one of the most jubilatory books for children in circulation. Each chapter ends badly, yes – the tortoise dies, the little girl is whipped or sick, people do not abide by Health & Safety regulations and are punished. But the important aspect of it is that for the 20 pages or so of each chapter Sophie does whatever she wants – deliciously transgressively, deliciously cruelly, deliciuosly darkly. What’s a punishment that takes place in two lines when 20 pages of text and illustrations have shown us the crime?

Didacticism is difficult to evaluate. I’m not exactly sure what Ms Browne is referring to here. That there is a moral lesson in many French children’s books is absolutely true, but that’s also true of many UK/ US books, and of many adult books for that matter. I don’t have much time for dubious comparisons as to who’s being more authoritarian than whom internationally. Darkness doesn’t lead to didacticism, just like lightness doesn’t preclude heavy-handed moral messages.

– The French publishing system is very different: authors are paid very little, there are no agents, and children’s literature is respected much less than in the UK/US.

All this is absolutely true, as I’ve written about many times in French as well as in English, for example here.

– There is no French Harry Potter.

We get to the dramatic statement that gave the article its title. ‘There is no French Harry Potter’. Incredible, huh? Let me observe that there is no American Tintin. There is also no Swedish Barack Obama. There is a flagrant lack of Egyptian Miyazaki.

This argument once again evidences the shameless anglocentrism of Ms Browne. She quotes, once again, someone very sympathetic to British interests – the Editorial Director of Gallimard Jeunesse, Christine Baker, who lives in the UK. I have nothing against the idea of quoting Ms Baker, but Ms Browne doesn’t give any voice to other publishers who don’t do their shopping in the UK/US as much, and who privilege French creation. I could volunteer my own, very respected publisher Sarbacane, which doesn’t have the same ethos as Gallimard, and invests much more in French authors than huge international bestsellers.

Now let me set this straight: I adore Harry Potter. Have I ever bemoaned the lack of a French equivalent? No! because this is a British story, not a French story. The great Tobie Lolness (Toby Alone in English), by Timothée de Fombelle, which she mentions, has nothing to do with Harry Potter. It’s a very lazy comparison, of the kind that people do when they say that ‘Hunger Games is the new Harry Potter‘.

Here it’s worth mentioning, once again, the hermetism of the UK/US market to translated books and the lack of recognition of foreign writing. Ms Browne seems to be saying that Toby Alone is one of the rare success stories of French literature in the Anglophone world. It isn’t. Yes, it ‘got an award’, but she forgets to mention it was an award for its translation, by the (consistently amazing) Sarah Ardizzone. Despite critical acclaim,Toby Alone remains virtually unknown in the UK.

Anyway, what Baker and Browne are saying is that there’s no big adventure story saga like Harry Potter in France. It’s true. Is that a problem? Only if you see this type of book as the be-all and end-all of publishing for children. UK/US publishers love big fat adventure stories because it’s part of the historical and cultural tradition of children’s literature here, and also because of Hollywood. Readers are used to these books. Of course, we read them in France too, but we simply have other literary traditions. Discovery of the day: France is not the UK or the US.

– Bayard is the best. ILU Bayard! Bayard <3

There’s one thing Ms Browne loves, though: Bayard Presse. Bayard Presse, as she explains quite well, is a big publishing corporation for quite high-quality literary and entertainment magazines for children:

The other area in which the French lead the way is children’s magazines. Since the 1960s, Bayard Presse has published first-rate magazines that take children from the cradle to university. Widely available at newsstands and supermarkets, titles such as J’aime Lire, Astrapi and Okapi are as intrinsic to a French child’s life as their creaky old classics. They contain a healthy mix of story-telling, science and craft-based activities, all aligned to the national curriculum.

She is right: most kids in France have had a subscription to J’aime Lire, Astrapi or Okapi at some point in their lives. And it’s great – I have wonderful memories of opening the monthly J’aime Lire, reading the novel and doing the games, and now that I’m grown up I’d love to write for them at some point.

But what she sees as a ‘healthy mix’ of various stuff I can’t help seeing as the relatively bland poor relative of the amazing, dynamic, constantly dazzling contemporary French fiction for children which Ms Browne seems to have no knowledge of. Bayard is nice and cute, but it’s not very radical, exciting or interesting. I’m not surprised she likes it, mind you – it’s exactly the kind of benign literature she seems to be yearning for.

But for the more adventurous-minded amongst you, and who are hoping to raise Frenglish kids on a diet of not-just-Charlie-and-Lola, here is a completely subjective selection of fun, exciting, witty, sweet, wonderful contemporary (1980+) books for young readers (picturebooks + early reading) in French.

NB: AS A GODMOTHER, I can testify that my goddaughter adores many of these books. She doesn’t prefer English picturebooks. QED.

- Gilles Bachelet, Mon chat le plus bête du monde, Seuil, 2004

- Gilles Bachelet, Madame le lapin blanc, Seuil, 2012

- Ramona Badescu & Benjamin Chaud, the Pomelo series, Albin Michel

- Sandrine Beau & Maud Legrand, La girafe en maillot de bain, L’élan vert, 2013

- Alice Brière-Haquet & Olivier Philipponneau, Le ballon de Zébulon, Auzou, 2010

- Alice Brière-Haquet & Lionel Larchevêque, La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes, Actes Sud, 2010

- Alice Brière-Haquet & Camille Jourdy, Le petit prinche, P’tit Glénat, 2010

- Alice Brière-Haquet & Csil, Paul, Frimousse, 2012

- Jacqueline Cohen & Bernadette Després, the Tom-Tom et Nana series, Bayard

- Philippe Corentin, Plouf!, L’école des loisirs, 2003

- Michaël Escoffier & Kris Di Giacomo, La mouche qui pète, L’école des loisirs, 2011

- Nicole Lambert, the Triplés series

- Jean Lecointre, Bazar Bizarre, Thierry Magnier, 2012

- Magali Le Huche, Le voyage d’Agathe et son gros sac, Sarbacane, 2011

- Thierry Lenain & Delphine Durand, Mademoiselle Zazie a-t-elle un zizi?, Nathan, 2011

- Alain Le Saux, the Papa/ Maman m’a dit series, Rivages

- Alain Mets, Ma culotte, L’école des loisirs, 1994

- Nadja, L’horrible petite princesse, L’école des loisirs, 2005

- Pef, La belle lisse poire du Prince de Motordu, Gallimard, 2010

- Pef, Rendez-moi mes poux!, Gallimard, 2010

- Yvan Pommaux, John Chatterton détective, L’école des loisirs, 1994

- Claude Ponti & Florence Seyvos, La tempête, L’école des loisirs, 2002

- Claude Ponti, Okilélé, L’école des loisirs, 2002

- Claude Ponti, L’arbre sans fin, L’école des loisirs, 2007

- Domitille de Pressensé, the Emilie series, Casterman

- Grégoire Solotareff, Loulou, L’école des loisirs, 2001

- Hervé Tullet, Un livre, Bayard, 2010

- Séverine Vidal & Cécile Vangout, Je n’irai pas!, Frimousse, 2011

- Séverine Vidal & Elice, Léontine, Princesse en salopette, Les P’tits Bérets, 2011

- Séverine Vidal & Guillaume Plantevin, L’oeil du pigeon, Sarbacane, 2013

Feel free to suggest more in the comments section… this is a purely spontaneous selection with no rhyme or reason to it.

For more info on French children’s literature (in French), you can always trust the excellent review blogs Enfantipages and La mare aux mots. Ricochet is the reference website for French children’s literature.

à bientôt!

Clem x

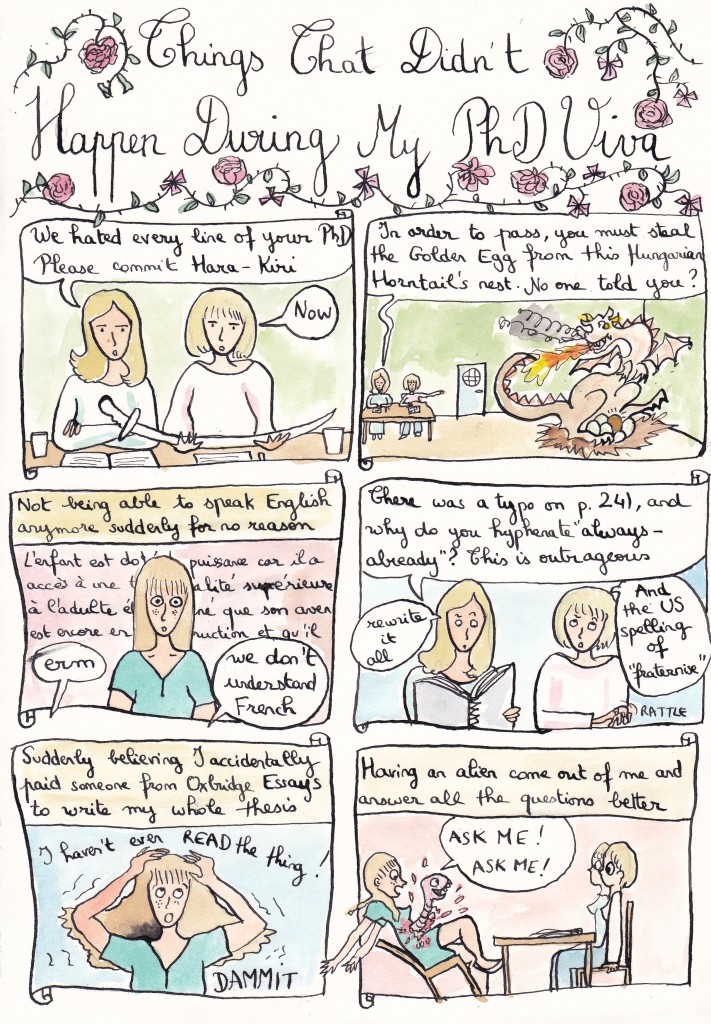

Or rather, ‘I’m not a PhD student, not yet a lecturer’. Ms Spears, shrewdly identifying the specific requirements for this predicament to end, further argues:

Or rather, ‘I’m not a PhD student, not yet a lecturer’. Ms Spears, shrewdly identifying the specific requirements for this predicament to end, further argues: