My ex-PhD supervisor (who, by the way, is currently writing an amazing abecedary of children’s literature theory and criticism on her own blog) always says to her young Padawans that they must always ask themselves ‘So what?’ about everything they write. Ask yourself ‘So what?’ at the end of your article on ‘Representations of octopi in adventure stories for boys, 1870-1912’, for instance. If the answer is, ‘Well… octopi! in adventure stories!’ then your article is useless and you might as well have spent a month and a half painting the borders of your nostrils with glittery felt-tips.

The implication, of course, is that by asking ‘So what?’ you will attempt to truthfully decide whether your piece is parochial, petty and only concerned with what it attempts to describe (bad) or has wider implications, for the study of children’s literature for instance (good).

This is even more important in actual published work than it is in MPhil and PhD theses. As William Germano says in his book From Dissertation to Book (helpfully recommended by Philip Nel), one of the main differences between a PhD thesis and a monograph drawn from the PhD thesis is scope: while a PhD thesis investigates a tiny aspect of Problem X, the monograph should attempt to make claims about the whole of Problem X.

This was never a problem for me, however, because I am blessed with ridiculous theoretical arrogance. So my self-questioning always went along those lines:

Q. Piece of work finished. SO WHAT?

A. So, existence.

Q. Another piece of work finished. SO WHAT?

A. So, meaning of life.

Q. Another piece. SO WHAT, this time?

A. So, everything about everything.

Q. We are so nailing this ‘so what’ thing!

A. Yeah!

When I had my PhD viva, however, the questioning went along those lines:

Examiners: When you say ‘existence’ here, don’t you mean ‘that little aspect of existence that may or may not be there for everyone’?

Me: No, no, I do mean the whole of existence.

Examiners: Are you sure?

Me: What will happen if I say I’m sure?

Examiners: You’ll probably fail your PhD.

Me: Ah then I guess I’m not sure. In fact, I probably do mean that tiny little aspect of existence that may or may not be there for everyone.

Examiners: And when you say, there, ‘this is something which concerns the whole of children’s literature and in fact every instance of every address to a child, anywhere in the world and for the whole of history’, don’t you mean, ‘this is something that concerns some children’s books’?

Me: No, I…

Examiners: Think of what we just talked about.

Me: Yes, I mean that’s something that concerns just a few books here and there.

Examiners: Good. Do you promise not to make all these grand claims again in your monograph?

Me: Gnnhh.

Examiners: Swear on the life of J.K. Rowling.

Me: Gnnh.

It wasn’t the first time this happened. All my articles rejected from academic journals are generally accompanied by comments along the lines of ‘This is clearly the work of a deluded and vaguely despotic individual who makes hilariously grand claims about everything from the analysis of two lines of an obscure picturebook.’

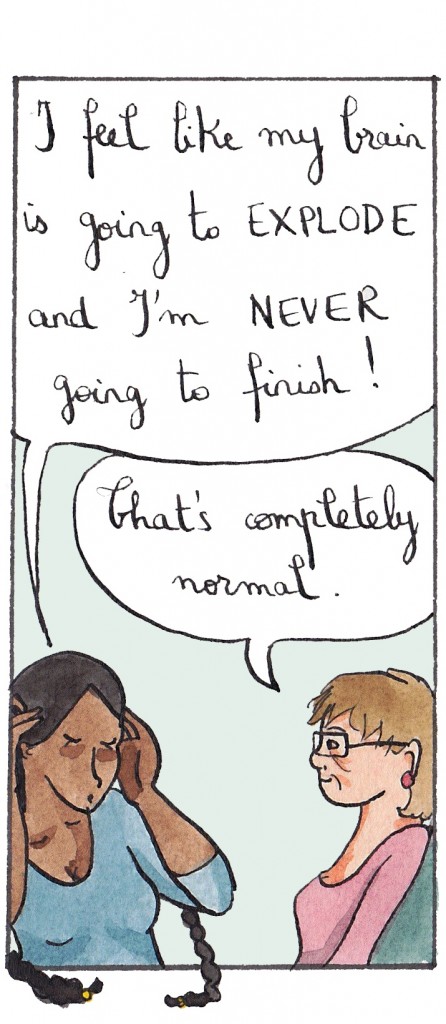

So now that I’m working on the monograph, I’m going through it all and thinking about whether my answers to ‘So what’ are still absurdly grand or whether I can get away with them. Unfortunately the demon of grand theorisation often wins over the angel of scrupulous criticism.

And I do believe in those grand conclusions that I’m now editing down or rectifying. I didn’t just put them there as a forced reply to the question ‘So what?’. I honestly think that I have good reasons to be making those claims, and if these reasons aren’t clear to the reader, it means I’ve failed at explaining them, not that they weren’t there to start with. So I endlessly edit the explanations so they lead more clearly to the Theory.

I can’t help it, I have much more patience for grand systems, grand theories, outrageous hypotheses, than for microscopic examinations of quite interesting properties of some texts. At least the former can fail spectacularly, whereas the latter will only ever achieve an uninspiring sort of success.

Well, that’s what I like to think, anyway. I wouldn’t recognise myself in a piece of work, however conscientious, that wouldn’t have those grand answers to that ‘So what?’ question.

No, I wouldn’t recognise myself, and that’s why this ‘So what’ question pertains to so much more than just research. I can’t just ask ‘So what?’ of individual pieces of writing. I also need to ask myself ‘So what?’ about the relevance of that writing to my own life. So what? Why am I doing this? What is the point? Is my existence being transformed by what I’m researching and writing? It very much is and very much has been, as I think it should.

‘So what?’ isn’t just a professional question about the impact of your research on the rest of the discipline. It’s a private question, one that interrogates your life project. What you research is a part of yourself, so what? So it must have an impact on you. The boundaries can’t ever be clear between the personal and the professional, between what you work on and what you are.

Well, so what?

so, existence.