Two Fridays ago at Homerton College, we had a day-long symposium on children’s poetry. It was supposed to mix creative and academic approaches, so there was an hour-and-a-half, wonderful poetry-writing workshop by Redell Olsen, who is currently the Judith E. Wilson Poetry Fellow at Cambridge.

We sat down in the orchard, and Redell gave us a series of writing exercises. Of course it involved writing, but it also involved taking in the space around us, the noises, the smells, the feel of the grass under our legs. Despite the brevity of the writing exercises, there was a kind of enforced patience in the workshop; an awareness of the world around, before and during the writing, an attention to detail, a weighing-up of possible options.

A lot of playfulness, too. Redell encouraged us [Green Party members may skip the next sentence] to pick up a fresh sheet of paper with each new exercise, and thus make each try just that – a try – and not a finished piece. Disposable writing, but not unimportant writing. Each try brought us closer to a personal mapping of the space we were in, of the sensations that it brought, and of their possible translations into literature or poetry.

I found this workshop truly revealing. I’m not a poet and I didn’t produce anything of any particular literary merit, but it shocked me to realise how fruitful it was to be able to write slowly, with breaks and pauses, with moments of observation.

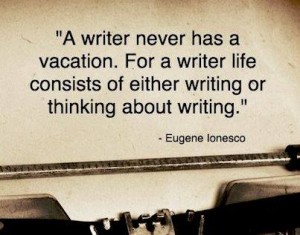

In my two jobs – academic and fiction-writing – I can’t write slowly. I mean this in all the definitions of ‘can’t’: I seem to be organically unable to; it wouldn’t be manageable anyway even if I could; and I’m not ‘allowed’ to.

I suspect my inability to write slowly comes from a lifelong cultivation of speed-writing. Writing fast puts you at a clear advantage at school and at university, and it’s an essential skill as a young academic since we have to publish so much in order to be employable.

The habit is so deeply-rooted that I can’t even remember a time when I wrote slowly. At school I always finished exams early, sometimes an hour before the end. Whether for academic or fiction-writing, I’ve never missed a deadline. You’re very happy with this productivity until the rather sinister realisation creeps in that you’re writing fast out of dutifulness or anxiety, rather than enthusiasm or passion.

Positive reinforcement: being ‘prolific’ is a compliment; publishers want you to write a lot; in academia, your list of publications is your best asset. The faster you write, the more you produce; if your work is deemed of good enough quality, and there’s a lot of it, you will elicit admiration and praise. That’s enough to prevent you from questioning whether you could write very well rather than just well if only you slowed down a bit.

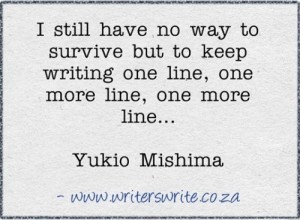

Anyway, even if you do start wondering about that, it’s too late. It’s a vicious circle: the more you produce, the more you must keep producing; and if people find your work satisfactory and are simply concerned with how much of it you can produce, there is no incentive to experiment with writing other things, or writing more slowly. So you just keep going at an increasingly insane pace.

You might feel you’re plateauing at some point, and that the quality of your work is more or less always the same. But as long as it’s not actively decreasing, and that people are happy – well, you just keep writing as fast as usual, if not faster.

It gives rise to a kind of academic or literary Fordism whereby you get better and better at spotting superfluity in your own writing, and cutting down everything you spend too much time on. You become extremely efficient, sure, but the time you manage to save is never truly earned back for Research & Development, so to speak – it gets immediately reinvested in Production.

In this you are encouraged by Twitter, Facebook and tales of who got hired where thanks to how many publications. Writing is your job, so you must produce writing; if there’s no writing, you’re not a writer or a researcher.

Writing slowly, experimenting with writing, gradually becomes ‘disallowed’, simply because you stop considering it as work. It’s a free-time activity. And I, like many people, have very little free time. I have a full-time research position, but I take on too much teaching, like everyone else, so I don’t do research 100% of my work time. And then my actual free time is mostly taken up by fiction-writing, which, of course, is itself mostly taken up by checking layouts, editing, liaising with editors, checking roughs – so, not-writing. And of what little is left I need to use a lot to do fake free-time-activities which are in fact linked to my two jobs, such as reading, writing blog posts, doing school visits, etc.

Writing slowly and experimenting with writing is just something I can’t do anymore. I would love to claim that the poetry workshop changed my life for the better, that I’ve now decided to slow down and to take the time to write and to play around with different academic and literary styles, but that’s not the case at all.

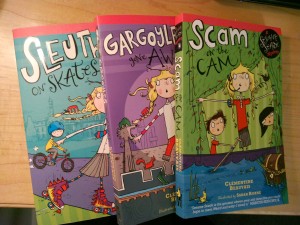

I just don’t have the possibility to do so ‘right now’, because I’ve got to check layouts for a British book, edit another British book and a French one, write two YA novels (English+French), finish revising my monograph, finish the article I’m currently working on, write another 2 before the end of July (French+English), and somehow I also need to fit in writing another children’s book before the end of the summer.

So I’ll write slowly ‘when I have the time’, which is, as it is for most people, never. My investments in Research & Development dwindle and dwindle and dwindle – but the production line is going well, thank you.

Clem