Dear friends, allow me to launch the most artificial way in the world of reviewing books: the Book Battle. Based on completely subjective judgements on my part as to which books are ‘similar’, I will, whenever I feel like it, ask two or more books to enter the ring, set a theme for the battle, and let them FIGHT. I will then name the winner. It’s a bit like Pokemon, but without the tedious slow-mo and psychedelic effects.

And today, ladies and gentlemen, please give us a big cheer for today’s contenders for the title of…

Best children’s book that parodies/ pastiches/ transforms/ readapts/ does something with much older children’s books (almost exclusively British and preferably of the Victorian or Edwardian era).

(bit of a mouthful I know; thank goodness I’m not actually giving out engraved medals)

VS

And the first fighter on the ring is The Willoughbys, by Lois Lowry! A heavyweight of children’s literature (she’s given us The Giver), Lowry’s crossed the Atlantic to be with us today with a tale of abandoned children, mothers and fathers lost and found, intertextual ecstasy and metafictional mirth. She’s also gone the extra mile and done her own makeup for this one. Aren’t the illustrations gorgeous?

But wait a moment before you put all your money on The Willoughbys, because it’s a sumo-wrestler of the publishing world that it will have to face: Dame Jacqueline Wilson herself with Four Children and It, an action-packed, fantastical-but-realistic family drama, just as self-referential and playful as its contender, and with even a few necessary readerly tears at the end.

Round of applause for our two brave fighters! Which book will win?

Make your bets!

And… they… are… fighting! The Willoughbys is the first to strike, and it seems to know where its strengths lie – humour. Just one or two pages in and the audience are already laughing their heads off. This parody of Victorian and Edwardian novels for children is packed with so many inconceivable disasters and misadventures that it’s almost impossible not to laugh at them… and at the ones it refers to. It’s not just referring to old children’s classics, it’s playing with them, laughing at them, mocking them. Four Children and It know it can’t quite match that – just a few smiles along the way, but it’s not its forte. We’re not trying to be hilarious! it seems to say…

The bell rings… and The Willoughbys get a point! Back to their initial positions…

But Four Children and It isn’t in the least discouraged. It’s now attacking The Willoughbys where it hurts: the social message! Look at Four Children and It – it’s not just a pastiche of E. Nesbit – it’s also saying something about the state of the modern family. Stepsisters, half-siblings, parents who don’t seem to care enough and others who care too much! How can The Willoughbys compete, when the child characters in the family are so stereotypical? And it’s done away with the parents completely – easy-peasy, anyone can do that. Where’s the reflection on family that really matters to children? The audience seems to approve, but…

… but The Willoughbys responds with the claim that it’s got a political message! It’s a feminist book, look at it – denouncing the hilariously traditional gender roles in the good old days. Four Children and It is a bit unsettled – it’s true that it says from time to time that boys don’t have to ‘act like men’ and that tomboys are what they are and it’s ok, but in other places the status quo is maintained – the general ideology is a little bit too ambiguous…

And the bell rings! The judges give one point to each book, and they’re back in their respective corners…

They’re looking at each other now, a bit shyly, hesitantly. Defensively. Why is that? Come on, attack! And it’s Four Children and It which launches the attack again, but not sounding very convinced. Ah, here’s why… They’re on the subject of whether kids who haven’t read the classic children’s books they’re both pastiching can still get something from the experience. Tricky question! And clearly they both have problems with it… The Willoughbys mutters and tutt-tutts, saying that come on, they’re classics, so kids will have heard of them, at least. And also the book has got a few pages at the end describing the stories of all the novels it talks about… and also, as an adventure in itself, it’s good, isn’t it? Four Children and It appears to its advantage – it’s only referring to one book, after all! But maybe that’s worse, retorts The Willoughbys, because then all the meaning is lost if the reader hasn’t read that one particular book. Four Children and It fights back: alright, alright! but it’s a good story too in its own right…

The bell rings, the judges are divided… After a few minutes of discussion, they decide not to attribute any points. The contenders are back to their initial positions. Their respective coaches, Lois and Jackie, feed them Powerade and wipe their front covers. And here we go – they’re back in the ring.

They’re both looking tired, their pages are a bit ruffled, but The Willoughbys strikes. The writing! Isn’t that the most important thing? It thinks it’s safe, on this point – after all, it’s full of splendid dialogue, wonderfully funny descriptions, and deliciously complex language, with a lexicon at the end. But Four Children and It dodges the blow. It can’t be attacked on dialogue – its dialogues are pitch-perfect, realistic, dynamic. And who needs complex language in a story set in the modern world? As for the descriptions, where in The Willoughbys can we find such mouth-watering enumerations of food, such sensual flourishes of delicate fabrics, such adorable depictions of tiny animals? It’s a child reader’s paradise, where The Willoughbys is so often talking to the adult above the head of the kid.

Ouch! That was a hard blow. The bell rings, and the judges attribute another point to Four Children and It. The two books are on their last legs now. The audience has never seen anything like it (books on legs, that is).

But The Willoughbys rises again. Let’s talk about the editing. Structure, structure, structure! Four Children and It is too long. It should have been edited down! (in the audience, a scandalised shiver traverses the Editorial Tribune). And look at it as object-book – it’s not illustrated, it’s big and cumbersome, nothing like the wonderful illustrations and all the editorial work on The Willoughbys. How can Four Children and It respond to that attack? It seems like it can’t. Honourably, it sits down again.

The bell rings for the last time, and the judges give another point to The Willoughbys!

The Willoughbys and its coach are jumping up and down. 3-2! By a very small margin, they’ve won! Confetti are raining down from the sky. Four Children and It quickly gets up again. Elegantly, the two ladies shake hands, and their books shake flaps. And it’s the Chief Referee’s role to announce that…

The Willoughbys has won the first Book Battle !

That will be all for today, dear readers. See you next time with other Books and another Battle!

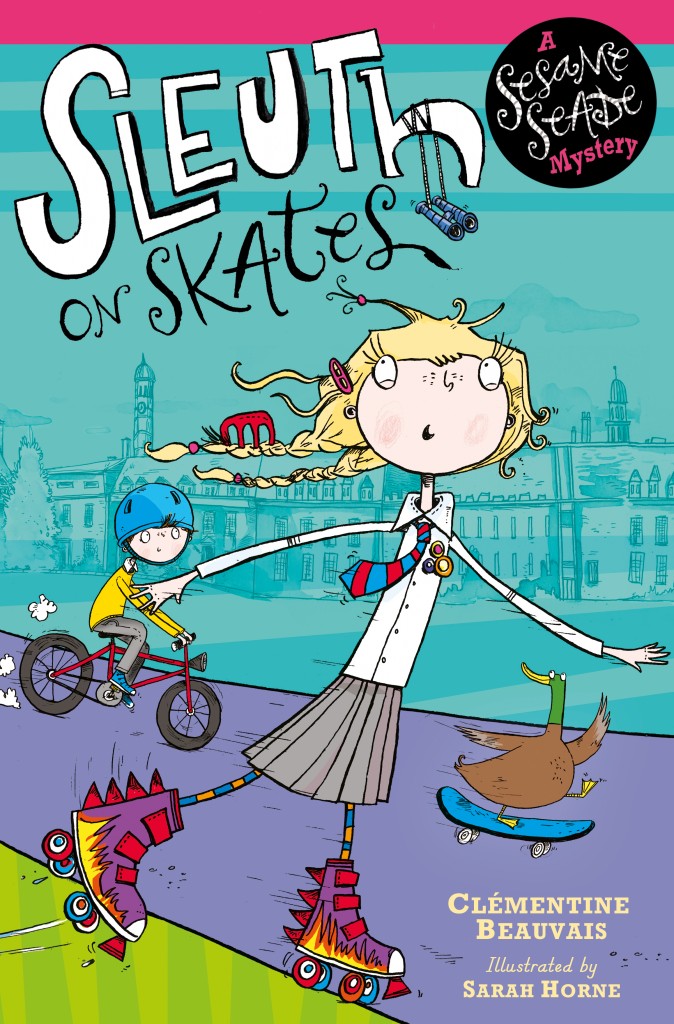

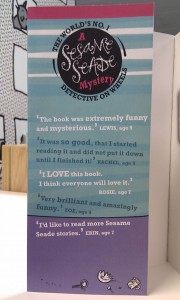

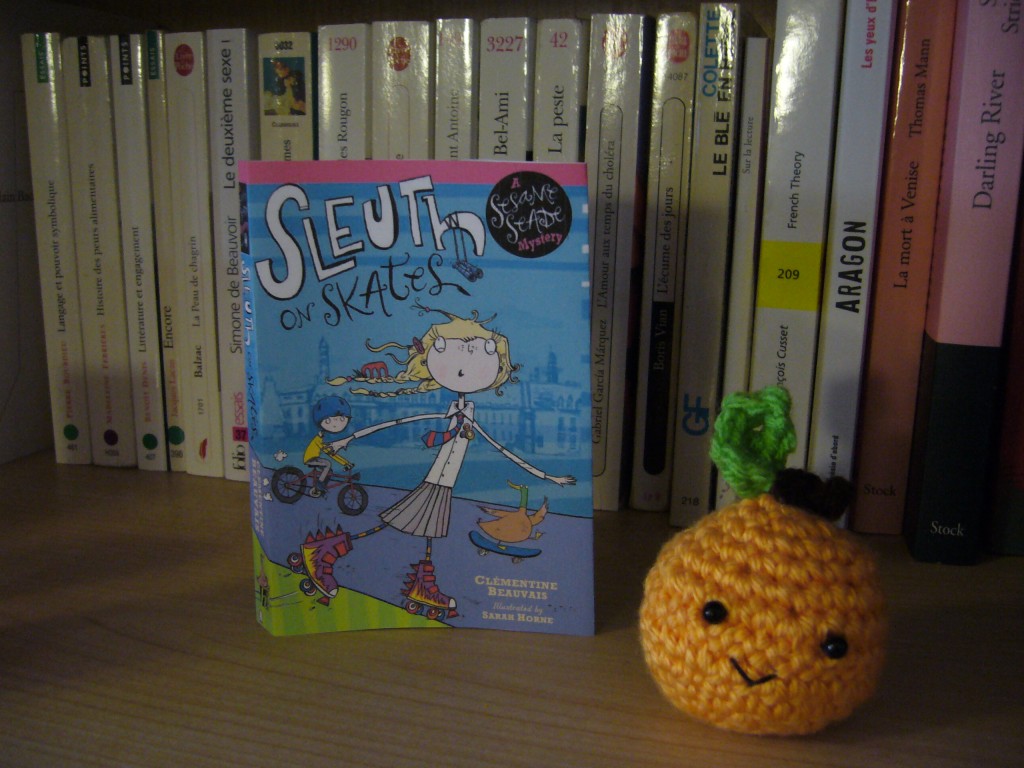

ve just finished writing the synopsis for the third novel in the Sesame Seade series, Scam on the Cam. Those things are never easy, especially with very intricate plots (I like very intricate plots), but they’re as necessary to a novel as IKEA furniture is to a new house. And that’s not the only thing they’ve got in common. Here’s more, in 20 ‘easy’ steps.

ve just finished writing the synopsis for the third novel in the Sesame Seade series, Scam on the Cam. Those things are never easy, especially with very intricate plots (I like very intricate plots), but they’re as necessary to a novel as IKEA furniture is to a new house. And that’s not the only thing they’ve got in common. Here’s more, in 20 ‘easy’ steps.