As a note to self, and to other people affected by the same problem.

Characters’ faces

The lovely Helen Fennell, in a blog post which you can find here, asks other readers if they actually ‘see’ characters’ faces precisely. She says, ‘faces seem to elude me for the most part, I imagine almost the “essence” of a person rather than any great detail’. She then goes on to wonder, ‘Do authors have a very clear idea of what their characters look like? Can they create an image in their head akin to a photo?’

And then asks (in the Britishest way possible): ‘If it isn’t too impertinent a question, what do you imagine when characters from books take their place inside your head?’

This topic chimed with me because I, like Helen, never see detailed characters’ faces when I read – nor when I write. This is all the stranger as, firstly, I’m a very visual person, an amateur doodler and an avid reader of comics, and, secondly, I ‘see’ places and surroundings in a very precise way, however little they might be described.

Unlike Helen, I’m not very easily influenced by film adaptations (though when a book is heavily illustrated, I’m influenced by the drawings), so the Harry in my head isn’t in any way Daniel Radcliffe . However, he isn’t either a very different person with precise features; his face is just a blurry ovoid thing, with glasses and a scar and a ‘shock of jet-black hair’.

I’m very sensitive to colour in my everyday life, and mildly synaesthetic (colour/ letters, /numbers and /sounds). Some characters are patches of colour rather than faces; this seems to be triggered by the writing style and atmosphere. Characters in novels by Colette, Beauvoir, Larbaud, Nabokov ’emit’ a lot of colours for me.

I’m very sensitive to colour in my everyday life, and mildly synaesthetic (colour/ letters, /numbers and /sounds). Some characters are patches of colour rather than faces; this seems to be triggered by the writing style and atmosphere. Characters in novels by Colette, Beauvoir, Larbaud, Nabokov ’emit’ a lot of colours for me.

In my own books, I very rarely describe main characters. There’s strictly no physical description of Sesame Seade in any of the books, for instance. For me, she wasn’t much more than a mass of hair whooshing around on purple rollerskates. When we were ‘briefing’ Sarah Horne for the illustrations, my editor called me to ask what Sesame looked like, and I didn’t really have an answer.

Yet when Sarah sent the first illustration, I immediately ‘recognised’ her. It was ‘as I’d imagined her to look like’, yet I hadn’t imagined her to look like anything specific.

French philosopher Clément Rosset talks about those moments when we think that someone looks like someone else, and then are incapable of saying who; we resort to saying ‘he’s got one of those faces’. Or when we see on screen an actor playing a character from a book, and we scream, ‘that’s not what she looks like at all!’. And yet we don’t have in our head any precise idea of ‘what she looks like’.

Or, we see for the first time the face of a radio presenter, and it can’t be them, surely not! That’s not the face we assigned to that voice. But what was that face? Not much more than a blur – but we’re adamant that it’s not that one.

This is, Rosset says, moments which evidence the ‘existence’ of invisible visions; an intimate conviction that we are referring to something (a perception, a thought, an image) when we are in fact referring to nothing at all, or not much. This ‘thinking about nothing’ is much stronger than reality, because reality is unfavourably compared to it: Daniel Radcliffe is much less Harry Potter than the not-much in my mind.

In Rosset’s view, which is connected to his wider theory of reality and its double, the invisible is eminently superior because it is ours, infinitely malleable, and always future; reality, in its visibility, is solid and boring. It is ‘the thing that we dream of when it is far, and which disappoints when it is close’ (45).

Rosset’s explanation, though, fails to explain why I, on the other hand, immediately ‘recognised’ Sarah Horne’s Sesame, and why I do sometimes (and I’m sure many of you do too) ‘recognise’ book characters in the form of the flesh-and-blood actors, with no or very little effort.

Helen is right to say that the ‘essence’ of the person (or character) is important. I ‘recognised’ the spirit of Sesame in Sarah’s drawing, and it’s precisely because I had no vision of her – because she was ‘invisible’ or ‘not-much’ in my mind – that the image was so cosily accommodated by my imagination.

What about when characters are heavily described? I’ve noticed that I tend to skip or not take into account physical descriptions. There are ideological problems, though, with this tendency. Infamously, the character of Rue in Hunger Games was at the centre of a racist storm in recent years when it emerged that she’d been Black the whole time. This was news to many readers, who had masterfully avoided the moments in the text where this was made clear. Rue had been by default white.

We’re often asked by students and pupils ‘who we would cast’ as our book characters (presumably also because many people think that having one’s book adapted into a film would be a writer’s deepest joy, and it’s very hard to convince them otherwise). Recently I did a school visit in France for one of my teenage books, where the students had ‘cast’ famous actors and actresses in the roles of the main characters, and asked me whether I agreed. It was an interesting exercise but I didn’t feel I could help much.

In the book, there’s absolutely no physical description of the narrator. Her name isn’t even mentioned. The teenagers had tried to imagine what she might look like. They’d had a poll in the class, saying how many people ‘saw’ her as having ‘short hair, mid-length hair, long hair’; ‘blond hair, brown hair, black hair’; whether she was ‘short or tall’ (she was by default white). They asked me for the right answer, but of course, I didn’t know.

In the book, there’s absolutely no physical description of the narrator. Her name isn’t even mentioned. The teenagers had tried to imagine what she might look like. They’d had a poll in the class, saying how many people ‘saw’ her as having ‘short hair, mid-length hair, long hair’; ‘blond hair, brown hair, black hair’; whether she was ‘short or tall’ (she was by default white). They asked me for the right answer, but of course, I didn’t know.

Just kidding? The latest academic ‘hoax’ and its consequences for cultural studies

The Sociology corridor of the French ivory tower is under siege: a few weeks ago, two academics pulled a rather uncomfortable prank on the academic journal Sociétés, by managing to place in the prestigious publication a ‘fake’, or rather ‘hoax’, article.

The story is quite complex, but to sum it up: two sociologists, Manuel Quinon and Arnaud Saint-Martin, wrote an article on the Autolib’ cars, which are electric cars available to the general public for short-time rentals in Paris (think Boris bikes, but cars). They submitted the article, entitled ‘Postmodern automobilities: When Autolib’ makes sense in Paris’ under a pseudonym to Sociétés, where it was immediately accepted and published. So far, so good; except that, as Quinon and Saint-Martin explained in a long and fascinating article, their analysis is a hoax, a hollow and meaningless text, full of – they say – ‘inanities’, written by scrupulously following the methodological and epistemological line of Sociétés.

To give you an idea of what the ‘hoax’ is like, here’s a representative sample from the introduction, translated by me (I’ve done my best to convey the academic ‘wordplay’, sometimes changing the ‘meaning’, but, as you shall see, the ‘meaning’ is pretty obscure anyway):

Automotive(s)

It is hard for the man in the street not to notice them: in Paris, the “Autolib’s” have now settled in the urban ecosystem. They do not fail to interrogate our relation to the city and to driving – a driving of/in the city. In many ways, they foretell a new paradigm. In this double movement of an electrified urban mobility and of a sharing of common vehicles, we indeed find at play a (sub?)terranean postmodernity. Although communication campaigns, political marketing and economico-industrial aspects escort the deployment of those little grey Bluecars® conceived by the Bolloré group, we can nonetheless note that they mobilise us, as much as we mobilise them: in the contemporary city, the sovereign subject gives way to the nomad, to the puer aeternus.

Because the flux of urban Lebenswelt is woven into a series of perfectly connected socio-technical webs, it is now indispensable to work towards a comprehensive, or rather “formist” sociology of (de)ambulatory contemporary sociality. […] We will detect in Autolib’ the mark of a libido mobilis, a libidinal self-centred energy, a kind of “subterranean centrality” which is literally automobilistic. All this expresses, maybe, the impulsive need to reconnect with a “je-ne-sais-quoi” which is that of the matrix, of originary, vital energy […] The Autolib’ indeed participates of the contemporary imaginal; it reshapes not just forms of sociality, whose tribal future goes without saying, but also contributes to the creation of a new “semantic pool”, for which we need to elaborate a hermeneutic sociology.

Phew.

The point, of course, was to ridicule Sociétés and a certain school of French sociology; to show that there is nothing in such studies behind a façade of jargon, preconceived ideas about contemporary society, and smattering of Deleuze and Derrida. As such, the researchers followed in the footsteps of Alan Sokal, a physicist who published in 1996 a prank article in cultural studies journal Social Text in order to denounce what were, according to him, the pretences and unsoundness of much French-theory-inspired American cultural studies.

Importantly, the hoax was also an attack on a particular person. Sociétés is headed by, and federates the disciples of, a charismatic Sociology professor called Michel Maffesoli. The ‘Maffesolian’ school of sociology (I would personally call it ‘cultural sociology’ or ‘cultural studies’) has a particular appetite for French-theory-heavy descriptions of everyday objects, practices and behaviours, basing their analyses on a conception of the ‘postmodern individual’ – a fragmented, non-rational and nomadic subject.

According to the two authors of the prank (and here I can’t take sides, knowing very little about the politics of French academia) Maffesoli’s influence on French sociology and on the media is undeserved, toxic, almost guru-esque. Worshipped by his disciples, who write article after article according to the ‘Maffesolian’ formula, the professor, they say, failed to notice even in his own journal the grotesque exaggerations of his own theory and concepts. Indeed, the hoax article goes to great lengths to celebrate the works of Michel Maffesoli with energetically sycophantic sentences, using what the two authors identify as Maffesoli’s key contributions to sociology: the drama of postmodernity, the meaningfulness of the quotidian, the hedonistic subject, ‘presenteism’, etc.

To sum up, Quinon and Saint-Martin’s aims with this hoax were to bring into disrepute Sociétés, Michel Maffesoli himself, but also, through him, the kind of sociological study that he represents. That is, as far as I understand the issue:

- Studies which emphasise everyday practices and objects, finding meaning in apparently meaningless familiarity;

- A jargon-heavy, French-theory-heavy, pompous language, relying on ‘keywords’ (buzzwords) coined by French and German theorists and/or Maffesoli(ans);

- Predictable conclusions, ‘confirmation bias’ for the school of thought’s vision of postmodernity;

- A strictly non-empirical methodology. The two authors are very clear that this was, to them, a major issue. Maffesoli’s motto appears to be that ‘no fieldwork’ is needed in sociology – so, in this particular case, there is no data collected on users of Autolib’s, for instance. Instead, the ‘empirical’ part of the sociological study should lie in the researcher’s felt experience of the studied object. The hoax article conscientiously respects this dismissal of fieldwork, explaining instead that the author ‘experienced’ the Autolib’, exploring what it ‘feels like’ to the driver. Of course, neither researcher actually bothered getting into an Autolib’ car; their ‘phenomenological’ approach was entirely imaginary.

- A sloppy peer-review process, letting through slapdash and absurd articles; it was later revealed that one reviewer had rejected the manuscript, but that the editor had gone with the positive opinion of the second reviewer.

The revelation of the hoax caused a modest but palpable stir in French academia as well as in the media, with Le Monde in particular amply covering the story (see also here and here). Michel Maffesoli, it was announced yesterday, has resigned from his Editor position at Sociétés, acknowledging that the article should never have been published, and that he had been careless not to have read it. But he refutes the accusations of intellectual sloppiness and academic mystification, denouncing what he felt was the ‘jealousy’ of Quinon and Saint-Martin; for Maffesoli, in short, this hoax is a spiteful attack on an eminent figure of sociological research from two frustrated younger colleagues.

Where does this leave us? Beyond the fact that the story itself is quite revealing of the legendary cliqueyness and ruthlessness of French academia, it is difficult not to feel uncomfortable when reading the hoax article and the accusations levelled at the type of sociology it represents. While there is no doubt that the article was profoundly silly, it raises an important question: to function as a hoax, was the article principally relying on 1) meaninglessness, or 2) ridicule?

Meaninglessness is easy to pinpoint. When the article states: “in the contemporary city, the sovereign subject gives way to the nomad, to the puer aeternus”, the use of the Latin expression is simply meaningless; ‘puer aeternus’ means ‘eternal child’; it makes strictly no sense in the context there; it is pure mystification.

If the article was entirely meaningless, it would be, in some way, less problematic: its publication could be put down to a tired reviewer and editorial oversight.

But it isn’t entirely meaningless. Instead, most of the article instead works as a hoax because it sounds, in some way, ‘ridiculous’. For instance, here’s the description of the use of the Autolib’ as opposed to owning a car:

No contract; just nomadism. No property; just use and reliance. No petit-bourgeois trophy, pretentiously exhibited to neighbours, parked/ parking class, sex and age identities, but a grey, floating medium, open to alterity, to différance as well as to differing views, silently and ecologically passing from a “high place” of the city to another…

There is certainly meaning in this extract. In fact, it makes a relatively interesting point: the Autolib’ allows the contemporary petit-bourgeois individual to be liberated from the cumbersome and ‘blingy’ external sign of wealth that a car represents, offering himself, instead, the luxury of a flexible and eco-friendly vehicle.

So why can it be considered ‘ridiculous’? For three main reasons, which I think can be categorised as ‘language’, ‘interpretation’ and ‘subjectivity’.

- Firstly, language: it plays on many clichés of French theory language and rhetoric: bizarre declensions of words separated by slashes or brackets (‘parked/ parking’), conscious misspellings heavy of Derridean extraction (‘différance’), random italicising, poor wordplay (‘différance’/ ‘differing views’ (‘différends’ in the original text)) etc.

- Secondly, interpretation, or rather overinterpretation: if the passage sounds ridiculous, it is in part because we are made to feel that the authors are overinterpreting a banal everyday object – that they are spending too much time and intellectual effort trying to decode and decrypt an object that isn’t there for that purpose. This is what many people who want to dismiss academic research call intellectual masturbation.

- Thirdly, subjectivity: the researchers having not done asked ‘real people’ what they think, their claim that the Autolib’ users are rejecting conspicuous consumption appears spurious; there might be many other reasons for not owning a car in Paris, including cost and general needlessness in a well-connected city.

The fact that most of the hoax’s power comes not from its utter meaninglessness but from the feeling that the language is vacuous and the study (over)interpretative and unscientific asks really quite problematic questions for cultural studies or cultural sociology scholars.

Let’s take language first. I am no French theory fan at all, and I understand the frustration that comes from ploughing through lines of undecipherable words, random puns and sporadic brackets. Some writers, like Derrida, are particularly annoying, because they are both eminently incomprehensible and worshipped by all the cool kids. It’s difficult not to believe that they’re all just pretending to understand and actually part of a worldwide conspiracy, like those people who thought the dress was gold and white.

But let’s have a little faith here. There’s no reason why academic language should be directly accessible. I do use thinkers who have specific jargon and sound difficult: Bourdieu, for instance, is legendarily obscure… at first sight. Once you get into it, and understand what it’s about, and read it carefully with the help of secondary texts, it’s not obscure anymore. It makes sense. The jargon makes sense.

I’m always very wary of attacks on jargon, because jargon is only ‘difficult’ if you don’t know the field. Jargon sums up decades of research in one word or expression. Once you know and understand it, a word of ‘jargon’ becomes a neat little package for years of intellectual work. It’s actually quite a beautiful thing.

But then, of course, what Quinon and Saint-Martin denounced is the empty use of jargon – they accuse the Maffesolians of quoting the necessary keywords with no knowledge of the texts and intellectual history behind them. If it’s this easy to mystify everyone, and to use keywords to hide a lack of original thought, then yes, we do indeed have a problem with jargon.

It’s particularly tricky in cultural studies because the jargon is ‘applied’ to everyday objects – so jogging becomes a way of being-in-the-world, washing-machines are a sublime object of ideology and dog-walkers are a new type of rhizomatic subject. The suspicion is strong that the ‘big word’ becomes a way of concealing the pointlessness of the studied object, and that the researcher is solely engaging in intellectual play verging on surrealism – Quinon and Saint-Martin actually compared their own hoax article to an ‘Oulipian exercise’.

This leads us to the question of overinterpretation, which is particularly stingy for people who, like me, have studied children’s books, comics, ludicrous social phenomena like the Mozart Effect, and routinely use secondary sources from newspapers, pop culture, visual culture and educational documents. This kind of (now not so trendy, but still sexy) research is based on the notion that these different types of discourse are equally worthy of interest. But the Quinon and Saint-Martin academic hoax seems to ask: is it ridiculous to study such things?

Reading it, I was reminded of those Amazon reviews of Mr Men picturebooks by a (bored and highly entertaining) parent with more than a smattering of literary theory. These reviews are of course hilarious, but, from the perspective of a someone who has just published a book on existentialist approaches to children’s literature, they can be a little uncomfortable:

An infant’s primer in Existentialism, we find in this book a weighty treatise on the personal politics of agency and empowerment, taking ownership and authorship of one’s own life. (Mr Bounce)

And many a children’s literature article from a Marxist perspective concludes to the conservatism of much children’s literature in the very manner of the Amazon reviewer:

In a thinly-veiled reference to the oppression of the workers by the ruling class, we are told that Mr Uppity is rude to everyone, and the detail that he has no friends in Bigtown explicitly informs us that the masses are on the brink of revolution. Are we about to bear witness to class war, Hargreaves-style? To see Mr Uppity brought to account by the revolutionary power of the proletariat? Vanquished and overthrown by the party of the workers?

Not so. Mr Uppity is no Marxian analysis, no Leninist prescription for class action. As always, Hargreaves’ inherent and essential conservatism comes to bear. His critique of the bourgeoisie comes not from the proletariat but from the feudal aristocracy.

Well, to be honest… he’s right. If there was a systematic study of the Mr Men series, it would probably be along those lines. Would such a study be ridiculous?

I don’t think so. I bemoan the lack of studies of highly commercial, ‘trashy’ children’s books like the Mr Men series; given their huge success, there should be more effort to study them. But researchers in children’s literature are understandably wary of studying such texts – they (and I include myself here!) prefer to study ‘good’ picturebooks, so-called postmodern picturebooks, because they are understood to have artistic and literary content – while the Mr Men series are principally interesting as a cultural studies/ popular culture phenomenon.

So in children’s literature for instance, there is a striking lack of scholarship on humour, on seriality, on chapter books; and a huge amount on highly sophisticated texts, realistic YA, political fiction (guilty) – which are by no means the most popular nor the most influential. Even authors like Roald Dahl or Jacqueline Wilson have been shockingly underresearched (there are exceptions, of course: much has been written on Harry Potter, dystopian YA, etc).

But it’s hardly surprising, given the amount of suspicion we’re under – by ‘we’, I mean people like me who are perhaps more interested in the cultural sociology than in the literary/aesthetic aspects of popular culture – when we study ‘banal’ texts. In an already-marginalised subdiscipline, we often don’t want to further marginalise ourselves.

Yet such studies can be immensely interesting and revealing, and should absolutely be conducted, however ludicrous it might sound to do a Butlerian critique of Gossip Girl.

Hoaxes like the Quinon/Saint-Martin article are useful to denounce specific people, journals and schools of thought, but also problematic because they weaken the credibility of an array of subfields – popular culture studies, media studies, film studies, video games studies, etc – which they didn’t actually target, but which are already constantly under threat because they sound ridiculous – which shouldn’t mean they are.

I’ll end with what Quinon and Saint-Martin denounced as a ‘non-scientific’ type of sociology. According to them, sociology proper should include empirical research and be strictly field-based. Maffesoli, again, refuted these accusations, by saying that he never understood sociology to be a science. According to him, sociology is ‘a knowledge’, and sociological research can absolutely stem from the researcher’s particular sensitivity to the world and interpretation of it; it doesn’t need to be ‘objective’ nor quantitative, as it is, again, not a science.

Here we need to remember that Sociology is in France very much still considered a ‘soft’ subject – Bourdieu described sociology in the 70s as the discipline picked by lazy middle-class kids with a charismatic disposition. So it is unsurprising that some sociologists should strive to establish it as a ‘science’.

But, however little I want to side with Maffesoli [EDIT: I’ve just seen that someone has tweeted this post ‘quoting me’ as saying ‘I side with Maffesoli’, which is completely absurd: learn to read, espèce d’imbécile], I agree with him that it is pointless to argue that sociology is a ‘science’, or at the very least to base our defence of the field on that claim; and (of course I would say that, being a non-empirical researcher) I certainly reject the notion that fieldwork is the only type that should be ‘valid’ in the field. This notion relies on an extremely naïve view of what constitutes internal validity, ‘objectivity’, and ‘data’.

Sociology, since its inception, has striven to downplay the ‘scientific’ portrayal of individuals as rational decision-makers, to transcend the objective/ subjective dichotomy, and to highlight the biases of any observation – ‘scientific’ of not. Its ‘data’, from the start, has been gathered from a wide array of various sources, giving a voice to types of texts that were not considered useful before. Internal rigour has been ensured not just through testing of hypotheses and replication (though of course many sociological studies do do that), but also through academic debate, intense work on concepts, multiple methodologies, a breakdown of the quantitative/ qualitative divide, and, yes, a phenomenological or even poetic approach to the world.

A lot of the most interesting work conducted in sociology is not falsifiable, not replicable, not, in short, Popperian in the least. A lot of it, specifically in the cultural subfields of sociology, is not scientific. Nor should it be.

There’s a lot of misunderstanding around what cultural theorists do. It’s quite similar to what cultural historians do: they might study the cultural and social changes brought by the democratisation of cycling in the 19th century, and we might do an analysis of the cultural and social changes brought by the Boris bikes now. Cultural historians do not do ‘fieldwork’, and similarly cultural theorists do not have to. They could – you could tackle the topic by doing a case study of Boris bike users, but you could also not do that.

It’s also quite similar to what literary scholars do, except that what is considered ‘text’ is more elastic, encompassing objects, practices, behaviours, etc. You can ‘read’ such things much in the same way as you read literary texts, focusing on their metaphorical content, on their aesthetic aspects, on their embedded ideological assumptions, on their history, etc.

If you don’t do ‘fieldwork’, and if you do use jargon, and if you do focus on the banal and the ordinary, it doesn’t mean you’re basking in your own ability to spout out caustic Barthesian analyses of anything under the sun, and despising the man in the street.

However, it could mean that, in certain cases; and that’s why academic hoaxes such as the Sociétés one are sometimes much needed.

On Charlie

I haven’t been here in a long time – my 2015 plans included living less in the now; leaving Twitter (you noticed, didn’t you? No? Thought so), writing fewer blog posts, not checking the news compulsively, and burying myself in good books and in work even more than usual.

But the Charlie Hebdo attack happened, and living less in the now sounds like a hollow decision. It was a huge shock for me and for the community of French and Belgian writers and illustrators who make up most of my Facebook feed. We did a strange kind of online mourning, talking, swearing, joking, breaking down, reading news articles communally, sharing good and also less good cartoons about the terrible news, ridiculing the cartoonists who clearly hadn’t understood a thing about Charlie and were drawing twee little children, nice gods, French flags and cutesy pencils, all of which would have been relentlessly mocked by the departed. But whatever, people express their sympathy as they see fit and their hearts are in the right place.

On the British side, it was quite hard for me and my fellow expats to read reactions on the walls of Facebook friends and articles in the press. Everyone condemned the attack, but there were many buts. I adore Britain, I chose to live here and I wouldn’t live anywhere else, but the cultural clash between Britain and France is much greater than most people who haven’t actually lived in both countries would imagine. In particular, ‘being left-wing’ is a very different thing here. ‘Being feminist’ is a very different thing. Even ‘secularism’ isn’t the same as ‘laïcité’, so technically I’m not a secularist, because even the National Secular Society is a bit too mild for my taste. I’m a laïcarde by default here.

The Charlie events exacerbated those differences. Many of the comments reflected what I already knew about incompatible beliefs and attitudes between the two countries. But there was also a lot of laziness in those reactions, with cartoons taken entirely out of context and read literally – idiotically – with no respect for the webs of visual and verbal references which would have been instantly recognisable to any French person. Us French lefties in the UK who liked Charlie Hebdo felt, all of a sudden, like we’d been outed as Daily Mail readers, which is pretty ironic.

Anyway, I thought I’d post here a few articles in English which reflect my feelings more or less accurately:

– My friend and colleague Olivier Tonneau’s hugely successful Comment Is Free column, and the original (and longer) version on Mediapart.

– Kenan Malik’s ‘Je Suis Charlie? It’s a Bit Late’ blog post

– Leigh Philips’s very developed argument, with comments on specific cartoons.

– Along the same lines, Lliana Bird’s article.

– Finally, it’s worth having a look at The Charlie Hebdo Cartoons No One Is Showing You.

I’ll be back here soon enough to talk about The Book, and about Other Things, I’m sure.

How I (barely) survived indexing an academic monograph

I have just spent the most wonderful week and a half of my life indexing my academic monograph. Few people, on their deathbeds, are reported as saying that they regret not spending enough time indexing their academic monographs; I feel there may be a reason for that.

Indexing, it turns out, is not only yawn-inducingly tedious; it is also much more difficult than I expected, and requires complete concentration. It is also one of these word-tasks which gradually empties all words of any meaning, to the extent that my book subtitle – Time and Power in Children’s Literature – now means stricly nothing to me, apart from the ‘and’ and ‘in’ that I didn’t have to index.

However, I must admit that indexing was also quite an interesting task in places, and taught me quite a few things about the way I write, the way I read, and the bizarre genre that academic monographs belong to. I thought I’d share a few insights about the painful process.

Firstly, just a few notes on the way it gets done (for me, at least):

- When I got my first proofs, I was asked to give two lists of entries (proper names, and nouns) to the publisher to constitute the index. My original list had roughly 300 noun entries. Because a software was going to be used to generate concordances, I had to submit several spellings for similar terms: not just ’empathy’ but also ’empathise’, ’empathetic’, etc. (so yes, ’empathy’ is now totally devoid of meaning too).

- Alongside the second proofs, the index came back with the page concordances. It looked a bit like this, everywhere:

désir et le temps 44, 49

desire 2–5, 7, 9–10, 19, 22, 27–28, 30–36, 39–41, 43–46, 49–51, 54–56, 58–59, 62, 69–71, 74, 77–79, 82–84, 86–95, 97–101, 104, 106, 127, 131–135, 139–140, 143, 153–154, 157, 165, 169, 172, 176, 178, 180, 186–193, 195–196, 199, 203–205, 207–209

didactic 2–4, 6–7, 9–10, 18–19, 36, 38–39, 41, 43, 46, 48–49, 53, 56–58, 63, 65, 69–75, 77–91, 93–94, 98–101, 106–109, 111, 117, 120, 122–123, 131–137, 140, 143, 147, 150, 152, 155–157, 161, 170, 176, 178, 184, 186, 188, 190–191, 194, 197–198, 203–204, 206–209

didactically 4, 156

Of course, the damn book being about children, children’s literature, and childhood, there were some particularly hellish lists of concordances for the terms in question:

childhood 5–11, 15–20, 22–25, 27, 34–35, 37, 40–41, 43, 46, 48–49, 51, 55–59, 71, 83, 85–89, 91–92, 96–97, 99, 104–109, 112, 114, 128, 130–131, 154, 166, 170, 176, 178, 180, 182, 186, 188, 192–195, 197–198, 205–206

child 2–11, 15–27, 34–36, 38–41, 43–44, 46–50, 52–65, 70–101, 103–110, 112–114, 117, 119–121, 123, 128, 130–131, 133–136, 143, 147, 150–152, 154–157, 160, 162–163, 166–188, 190–209

child reader 2–4, 7–8, 10, 40, 47–48, 58, 63, 71, 73–74, 78–82, 91–92, 94–100, 112–114, 117, 128, 130–131, 133, 135–136, 143, 147, 150–151, 154, 156–157, 160, 162, 167, 169–171, 174, 176, 179–180, 182–183, 198–203

children’s literature 2–9, 15–20, 22, 25–27, 33–34, 40–41, 43, 46–59, 62, 65, 70–72, 74–75, 77–81, 85–86, 89–91, 94–100, 105–106, 108–113, 118, 122–123, 131–135, 147–156, 161–163, 169–171, 174, 178–186, 192, 195–198, 202, 204–209

- I sat down with much tea, for days and days on end, and went through the proofs, and slowly cut down, merged, subdivided and split those ginormous lists of page numbers, using subentries. I Ctrl+F’ed by way through the electronic proof instead of printing out a paper proof, because 1) trees are dying and 2) it’s much easier.

So what did I learn, dear readers?

- Some concepts are just too damn large

I was primordially mystified about one thing: how do you index a term that is quite literally central to the whole book? In my case, it seemed difficult to index ‘time’, ‘power’ and ‘children’s literature’ in any other way than by saying ‘Read the whole damn book, you lazy sloth’.

I sought inspiration in academic monographs I happened to have lying around, such as Peter Stearns’ (excellent) Anxious Parents: A History of Modern Childrearing. How, I wondered, did Stearns index the term ‘anxiety’?

![]() That’s right. Eight page numbers or ranges. I was pretty sure I’d seen the word ‘anxiety’ or ‘anxious’ something like a hundred times more throughout the book, but I was curious to see which occurrences Stearns had decided to index.

That’s right. Eight page numbers or ranges. I was pretty sure I’d seen the word ‘anxiety’ or ‘anxious’ something like a hundred times more throughout the book, but I was curious to see which occurrences Stearns had decided to index.

So I checked. And apart from an introductory bit (p.11) and a conclusion bit (215-216, 222) which were vaguely about definitions of anxiety, the other choices of pages were totally incomprehensible. Why pick those? I have no idea. If I had done Stearns’ index, I would have had subentries of the type: ‘health-related’, ‘about achievement’, ‘class-related’, ‘definitions of’, etc. An entry like this is of no use at all.

But at the same time, the truth is – as a reader, I didn’t care. I have a book in my hands called Anxious Parents. I read it from cover to cover, in part because it’s quite an entertaining book, and also because I needed the whole of it. I didn’t need to refer to the index to tell me where to find bits about anxiety. Still, it wasn’t a very satisfactory entry.

Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble has a nice, very detailed entry for ‘gender’, but then random entried here and there: for instance, ‘reality of gender’, and ‘construction of gender’, which are not cross-referenced under ‘gender’. I don’t know why.

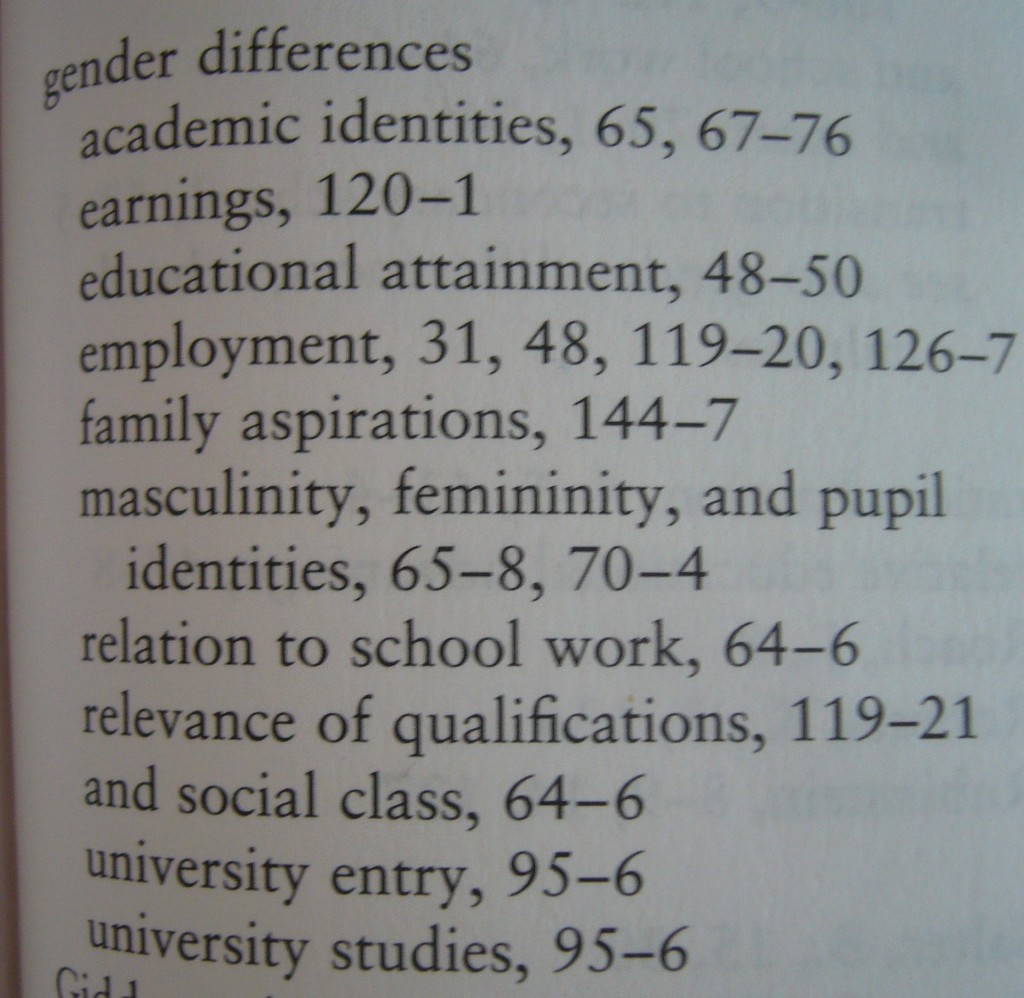

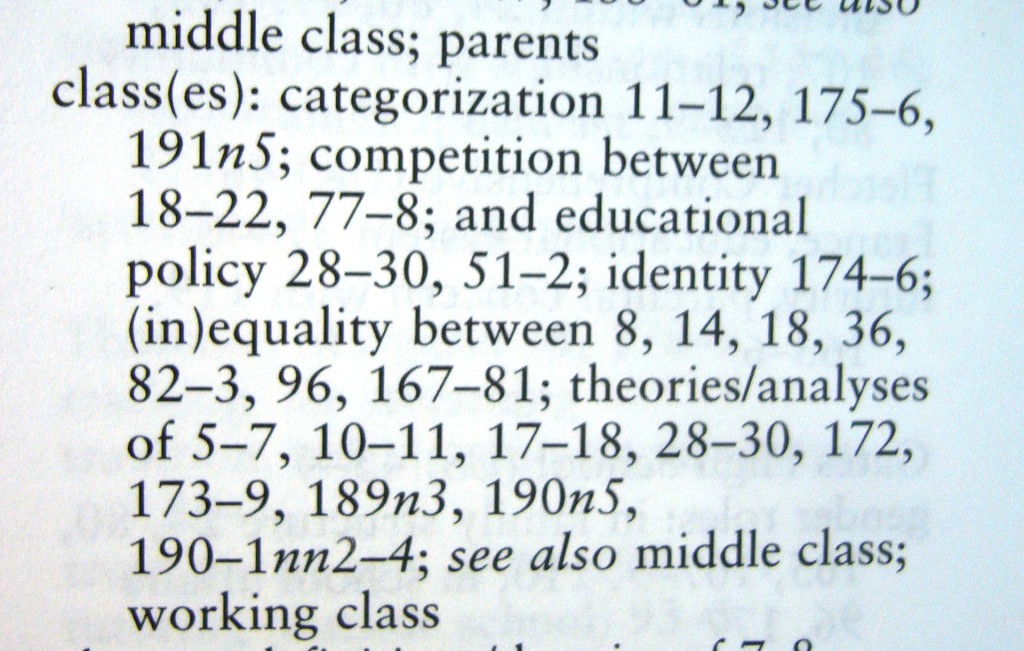

I then opened Stephen J. Ball’s Class Strategies and the Education Market, and looked for, well, ‘class’:

Quite a lot more detail here. This is a pretty good entry, I thought – clear, broad enough subentries, cross-referencing with middle and working class, which sounds very logical. However, having read the whole book, I can’t help but feel that frankly, Ball’s thoughts on class would be quite simplified and decontextualised if I were to simply pick my way through it thanks to the index.

Quite a lot more detail here. This is a pretty good entry, I thought – clear, broad enough subentries, cross-referencing with middle and working class, which sounds very logical. However, having read the whole book, I can’t help but feel that frankly, Ball’s thoughts on class would be quite simplified and decontextualised if I were to simply pick my way through it thanks to the index.

But then again, it wouldn’t have occurred to me before to use an index to look for the central concept in a book. Who does that?? And suddenly a new diabolical thought came to my mind:

- Sometimes, you just don’t want to help the reader.

Seriously: do I want my readers to pick their way through the central concepts in my book?

Sure, I could put a subentry to ‘children’s literature’ saying, for instance, ‘definition of’. But that’s just asking the lazy reader to read just that definition and not take into account the pages and pages and pages of articulate and cogent reflection (sure) that have led to it.

By that time I was fuming, hungry, bored (and also getting dozens of hate emails per minute, but that’s another story) and ready to strike out at those virtual bad readers of the book I was imagining. I spent hours on those pages and pages of articulate and cogent reflection, you scroungers!

I suddenly felt like my index was exposing my poor little book to immoral cherry-pickers, ready to quote definitions entirely out of context. At the same time, I couldn’t quote a whole range of pages before the definition, or it would confuse the hell out of the immoral cherry-pickers and they’d close the book.

So I wanted to help some readers. Just not all readers.

Eventually, I decided to keep it broad and clear like in Ball’s book, but with subentries obscure enough that they couldn’t be relied on entirely out of context; ‘childhood’ became, for instance,

childhood temporal otherness of 6, 15-20, 22–25, 56-58, 71, 104-108, 150, 170, 194; symbolic 7-11, 40–41, 55-56, 71, 85, 88, 154, 170; as associated to hope 46-48; in the didactic discourse 85–89; and subjectivity 96–97; Beauvoirian approach to 104–108, 112, 192–195.

- You can really have fun with some entries

This is something I wouldn’t have believed in the first few hours of the terrible task, but I realised that some entries at least offered elegant narrative possibilities. Specifically, the not-huge-but-still-quite-important-concepts. I’ll give you my favourite one here:

disempowerment of the adult 3, 7, 57-58, 65, 113, 124-131, 205; of the child 17–18; of child and adult 176-178, 190 see also power

I’m proud of this one because it’s quite clever. You see, the whole book is about how children’s literature is not as disempowering for the child as much children’s literature theory seems to think it is (see previous article for more details). In fact, in my analysis, children’s literature, more often than not, betrays an adult lack of power.

So this little entry indicates quite neatly what happens in the book: ‘disempowerment of the adult’ has far more page entries than ‘disempowerment of the child’, and the last subentry (‘disempowerment of child and adult’) indicates that we’re talking here about a phenomenon that is also common to both.

I’ve managed entries like that here and there, but not as many as I’d like; they’re my favourite, and if they were little puppies I’d pat their heads and give them treats.

- Those horribly overlapping entries!

Inevitably, some entries are going to overlap. You can’t talk about ‘time’ without it overlapping with ‘futurity’, or ‘existence’ without it overlapping with ‘existentialism’. In a way, it could be worse: I actually discovered, doing the index, that I’m thankfully not too bad at using words rigorously enough that I don’t use different ones to mean the same thing (thank you, French education of torture and trauma).

But even so; the worst entries were ‘power’, ‘might’ and ‘authority’, because in my book’s theorisation, ‘power’ is split into two kinds : might and authority. So how do you index those and cross-reference them? And how do you make sure that people are actually going to look up ‘might’ and ‘authority’ instead of just ‘power’?

Well, I created a very inelegant subentry for ‘power’ which I called ‘dynamics of the adult-child relationship’ and which contains a lot of page numbers; and then I finished that subentry by saying ‘see also authority, might’; which I also did for ‘authority’ and ‘might’.

It feels redundant and awful; but it makes sure that a reader will look at authority and might. Since ‘power’ is a central concept in the book, I want to force the reader out of this entry through sheer boredom of all those numbers. The ‘authority’ and ‘might’ entries are much clearer and more reader-friendly, so the reader will jump on those instead.

That was, at least, my reasoning. Maybe I have a manipulative personality, or I’m good at mind games; you decide.

- How specific should the subentries be?

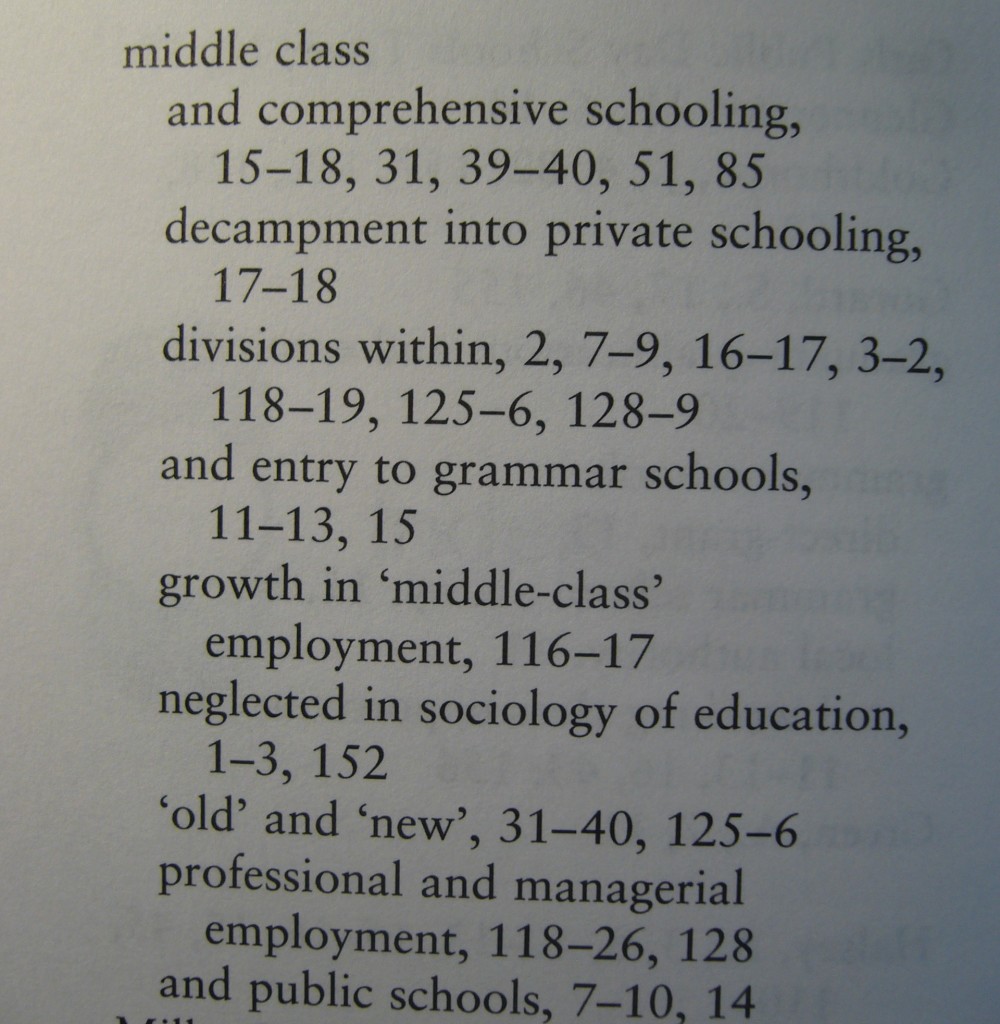

From Stearns’ completely nonspecific entries to a complete avalanche of subentries, my bookshelf was full of different approaches. If you want to get an index-inferiority-complex, Education and the middle class, by Sally Power et al, is your book:

Note the final ‘university entry, 95-6’ and ‘university studies, 95-6’. That, my dears, is commitment to indexing.

But seriously, it can get a bit surreal:

‘neglected in sociology of education’? Really? Do we need this entry? Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s a good idea that it’s there, but the implications are shudder-inducing. Should I have a subentry saying ‘unnecessarily guilt-tripping the child into saving the environment’, under ‘ecological books’? There seems to be no limit to where this kind of subentry can lead you – you might as well rewrite the whole book in index form.

‘neglected in sociology of education’? Really? Do we need this entry? Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s a good idea that it’s there, but the implications are shudder-inducing. Should I have a subentry saying ‘unnecessarily guilt-tripping the child into saving the environment’, under ‘ecological books’? There seems to be no limit to where this kind of subentry can lead you – you might as well rewrite the whole book in index form.

As you can see, this week and a half in the circles of hell has triggered some half-annoyed, half-intrigued reflection on the matter. Above all, it’s made me think that I can’t imagine giving the job to anyone else: at least for an academic monograph, you really need to know the whole damn book by heart, and only one person is sad enough for that: the author.

‘Open Access’, 1. The Problem of ‘Power’.

Outreach, impact, open access – as academics, we’re constantly asked to make our research accessible to the general public, sometimes at great cost to us, whether in terms of time or of money. The latest obsession is with articles in open access. But I doubt many people who aren’t academics in the fields (and, to be frank, few people who are) would actually plough through many jargonny articles in their published form. Academic writing is hard; it makes assumptions about things you’re already supposed to know, because it mostly addresses people in the discipline.

So ‘opening them’ to everyone may be a start, but if few people can understand what’s in them and why it’s valuable without having at least done an undergraduate module on the subject, what’s the point? I’ve got absolutely nothing against jargon – people who are always complaining about academic jargon don’t realise that they all have jargon too in their own professional lives, which simply becomes transparent because they’re familiar with it. Jargon is just a battery of terms that make sense to people who know them. It’s not evil, it’s useful. But it is exclusive, by definition, and to make something ‘accessible’ you need to strip it of jargon – which means going through everything that lies underneath those terms again.

A nice solution to ‘open access’ that would actually make articles accessible – not just downloadable to your computer, but actually understandable –would be for academics to produce, every time they publish an article or a book, a jargon-free, simple summary of what it’s ‘about’, which readers could read to whether or not the article itself is accessible. Interesting exercise, too… I’ll try to do it here.

________________________________________________________

I’ll start with an old-ish article of mine, ‘The Problem of ‘Power’: Metacritical Implications of Aetonormativity for Children’s Literature Research’, which was published in Children’s Literature in Education in 2012. (The link goes to the journal website, which won’t help you if you don’t have access, I know.)

Let’s begin with…

1. The Title

(Yes, Massive Jargon Alert.)

‘The problem of power’: whatever comes before the colon can generally be ignored. It’s here for decoration, and will all make sense later.

‘Metacritical’: this is a term we use to mean that we’re being critical about our own critical practice. E.g: if I study a Jane Austen text, I’m doing criticism. If I study a whole body of critical texts about Jane Austen, I’m doing metacriticism. Yes, it may sound crazy to study ‘what other people have said about Jane Austen’, but it’s a major way of progressing as a discipline.

So here when I’m talking about ‘metacritical implications’, it means things we need to take into account when doing further criticism.

‘Aetonormativity’: This is children’s literature-specific jargon. I’ll get back to it soon.

‘Children’s literature research’: referring here to the literary study of texts written for children.

So the title means that there’s something about the concept of ‘aetonormativity’ – which I explain below – which should make us cautious when we analyse children’s books.

2. What’s the situation?

The article revolves around the concept of ‘aetonormativity’. Aetonormativity is a term invented by major children’s literature scholar Maria Nikolajeva and developed in her book Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers (2010). She’s written about it on her blog here, but I’ll sum it up here too:

Aetonormativity means the existence of an age-related norm: in this case, the norm of adulthood. In the Western world, when I say ‘a person’, this person will probably spring to your mind as an adult. Our society is organised with a vision of the ‘normal’ individual as an adult – from sizes of bus seats to the provision of special ‘child-friendly’ spaces (no one needs to tell you that the street is ‘adult-friendly’). Children, who are not yet adults – not yet ‘normal’ – cannot work, drive or vote, and they get special rights too and special protection. Children are the ‘other’ – here ‘other’ is academic jargon to mean a deviation from the norm.

Nikolajeva’s invention of the term is specifically in relation to children’s literature. In texts for children, she says, there is always an assumption that adulthood is the norm and that the child is ‘other’. Children are portrayed as lacking, as not-adults: not-working, not-sexual, not-mature, etc. Children’s texts are thus, most of the time, aetonormative.

Two important things here:

1) This term is inspired from other theories, in particular queer theory, which says that, in our society, heterosexuality is seen as the norm and homosexuality as the ‘other’ sexuality. It comes from a long history of research in other fields trying to highlight problematic power positions: Marxism, feminism to name only a couple.

2) Nikolajeva isn’t the only scholar to think that children’s literature is almost always aetonormative (= presents adulthood as ‘norm’ and childhood as ‘other’). This idea had been steadily growing in children’s literature research since the 1980s.

3. What’s the ‘problem’?

The ‘problem’ comes from the fact, as I see it, that many pieces of research which focus on the aetonormativity of children’s literature (= on the fact that it presents adulthood as a norm) tend to conclude that it means that children’s literature reinforces adult power. What I argue in the article is that we can (and indeed should) accept the general aetonormativity of children’s literature, but not conclude that it systematically disempowers the child.

This needs to be unpacked a little bit. Outside of the adult-child relationship, in most cases, the link between power and norm is quite logical. Being the ‘other’, the ‘different’, the ‘not-normal’, puts you in an underprivileged position. If you’re still surprised when you hear of a female CEO, it’s because you don’t take it fully for granted that women should be CEOs; because the ‘normal’ CEO implicitly comes to your mind as a man. Women need to overcome greater obstacles than most men in order to become CEOs, from individual to institutional prejudice.

However, what I argue in the article is that the child-adult relationship is not the same as the relationship between adult women and adult men, or between able and disabled adults, or between adults of different ethnic or socioeconomic backgrounds. They certainly have features in common, but also central differences.

4. What makes it specific?

As I argue in the article, adults and children have different time frames, different temporalities, associated to them by culture, language, representations.

In brief: adults are of course powerful in some sense because they have a lot of ways of controlling children, and their power stems greatly from the fact that they’ve been alive for longer: they’re said to have ‘experience’, ‘authority’, ‘responsibility’, etc. However, and this is what I’m arguing, children are also perceived as powerful by adults – even though we may not want to recognise it – because they have a longer time left to them to act.

So perceptions of children by adults are associated with a vocabulary, metaphorical or not, which does express a specific kind of power: ‘potential’, ‘hope’, ‘promise’, etc. That power is future-bound, turned towards ‘tomorrow’, while adults draw their specific symbolic force from the fact that their time past is longer.

And too often, in research, the term ‘power’ is used to encompass everything – as if adults had all the dominance and children had nothing. Hence ‘the problem of power’. By using the term ‘power’ without defining it (and I say in the article that it’s rarely defined), we obscure forms of child power.

There are other differences between adult and child powers, I’m sure, but from my perspective this is the one that interests me: the difference in temporality which leads to different kinds of power.

I call adult power ‘authority’ and child power ‘might’, or potential – a power for the future, in opposition to the adult power which comes from the past.

I should say that this difference is to a great extent socially constructed, which means that there’s little about it that’s ‘natural’. Instead, this difference is mostly symbolic, having been fabricated, so to speak, by culture and society. Sure, children are factually younger than adults, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they should be perceived as having more potential. For instance, at a time when children often died before their twelfth birthday, it might not have been as prominent to think of them as full of potential.

5. OK, so children will (probably) live longer than adults and therefore are seen as having more potential; so what?

Well, firstly, it’s important to say that this difference – however basic it may sound – is actually not articulated that often in research, at least not to the extent that we can truly see that it’s a kind of power that the child has. Maybe because it’s seen as self-evident, but perhaps also because – as I argue in the article – well… maybe because we quite like, in fact, to think of us adults as more powerful.

Here’s the contradiction: the more we deplore that children’s literature is oppressive for the child and shows adult power over children, the more we manage to convince ourselves that it’s true – and the less we’re able to see child-specific forms of power.

Our positions as researchers are important here: we’re all adults. And we need to be conscious that it’s seductive for us adult researchers to keep repeating that adults are in power and children aren’t. Maybe we’re trying to avoid saying that actually, like most adults, we are a bit in awe of what children can do in the future and we can’t (because, to be brutal, we’ll be dead while they’re still alive).

So, in short, what I’m saying in the article is that aetonormativity (= the norm of adulthood) doesn’t lead necessarily to an excess of adult power, because there may be an ‘other’ power, that of the child (‘might’, ‘potential’). So when we talk of children’s literature as aetonormative, we must be careful not to obscure the child’s share of power; because, in the case of the adult-child relationship, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the ‘other’ is also ‘disempowered’.

This is where the article stops, but it’s a statement piece which accompanies all my later work, in particular in my academic book, which is coming out in January. In that book, I build up on the distinction between ‘might’ and ‘authority’ and I show how children’s books which apparently express adult ‘power’ actually make space for the child’s unpredictable action, his or her ‘potential’, in the future.

_______________________________________________

Phew! That was much harder than I thought it would be. It’s interesting because I thought that, since the idea at the centre of the article is quite simple – ‘children also have power, you know! They will be alive when you’re dead!’ – it would be the easiest of my articles to summarise. But no – it’s difficult to get there without having to go through everything in literary and cultural theory since the 1960s… and also without talking about children’s literature theory and criticism since the 1980s. I probably also made assumptions about a number of things – childhood and adulthood as constructed categories, for instance – which I shouldn’t have.

I might do a few more of those and see how it goes.

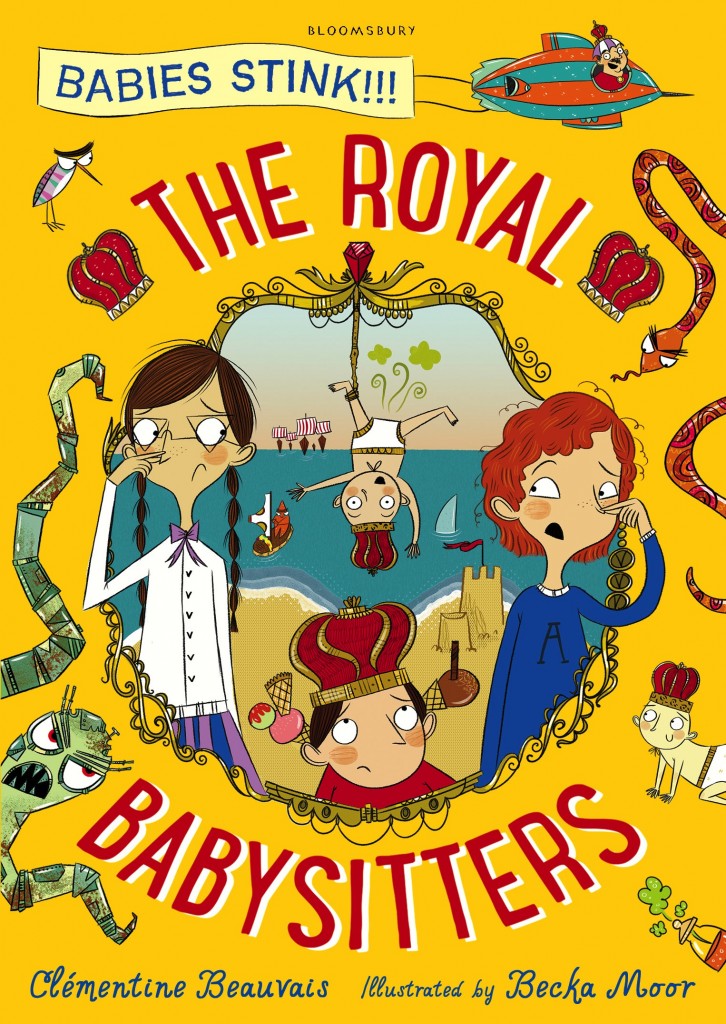

A Very Royal Book Birthday

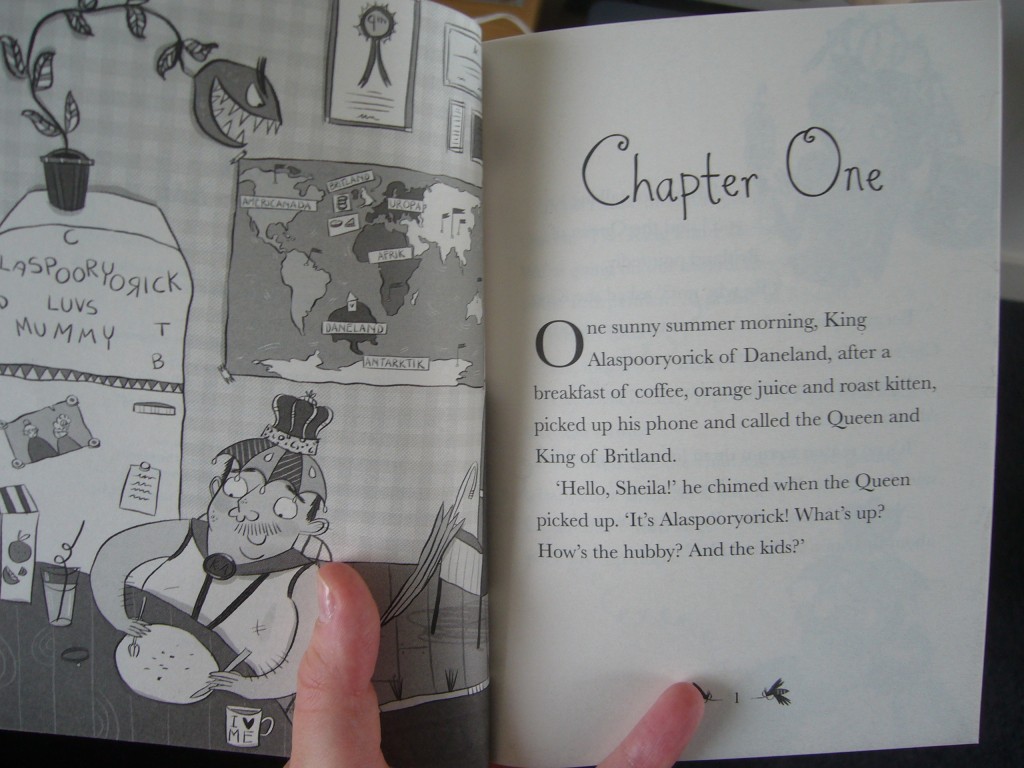

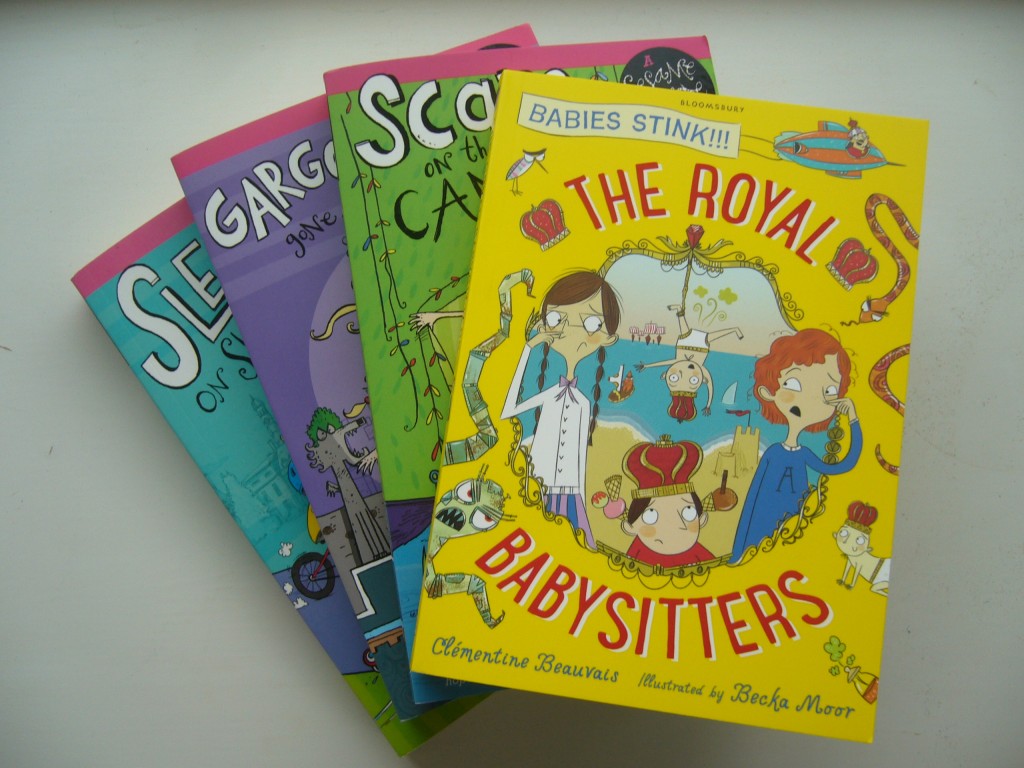

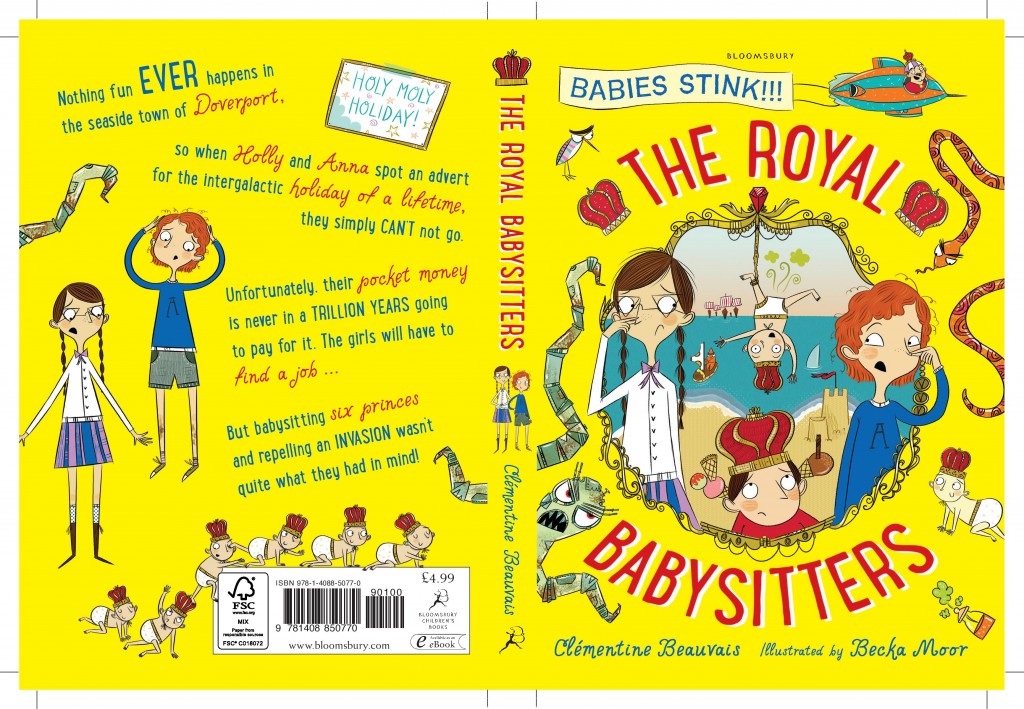

Happy book birthday to The Royal Babysitters, which is coming out today with Bloomsbury and illustrated by Becka Moor!

The Royal Babysitters is basically a secret ode to royalty and to the benefits of earning money through hard work from a very young age. Yep, that’s me, monarchy-worshipping and dirty capitalist all the way.

It’s all about little Anna and Holly Burnbright, who are not so happy with their forced staycation (they’re not very rich, because their dad disappeared years ago in the beak of a pelican, and their mum is a writer of ABC books paid 1 pound per letter). And it gets worse when the two sisters spot an advert for an incredible Holy-Moly Holiday involving volcano scuba-diving and baby-elephant polo.

Therefore, they have to find a summer job to buy tickets to that holiday.

A summer job comes in the form of royal babysitting: it so happens that today is the King and Queen of Britland’s annual day of leave to the Independent Republic of Slough, and they need someone to look after their rather energetic princes. Anna and Holly are ideal for the job (well, they aren’t, but no one else wants to do it.) At the Royal Palace they meet the charming little Prince Pepino, who’s not exactly the bravest prince in the world but has a cool felt-tip-drawn watch on his wrist that always says it’s ice-cream time.

As if their job wasn’t complicated enough, King Alaspooryorick of Daneland, who’s always been jealous of the King and Queen of Britland’s indoor swimming-pool and cellar full of Francian cheeses, has decided that today is the perfect day for an invasion.

Will Pepino, Anna and Holly manage to repel the invasion?

Will all the princes survive?

Will the Royal Cow be refrigerated in time?

Will King Steve of Britland manage to jump from the highest diving-board at the swimming pool of the Independent Republic of Slough?

You will know the answers to all these stressful questions if you gift the book to a young human and then read it to him or her (doing a big voice for King Alaspooryorick, a little peremptory one for Anna, etc.; and making it sound animated and hilarious; I trust you are fully able to read a book out loud to a child in an interesting way, or else they might not find it funny and all my efforts will be ruined; so please do your best.)

You can even read the first four pages, look:

The second book in this perfectly nonsensical series will be called The Royal Wedding-Crashers, and will come out in April 2015. In the meantime you may reread The Royal Babysitters a thousand times, or pick up the Sesame Seade series (DOUBLE PROMOTION BLOG POST ALERT).

Or plan your own invasion of some faraway land.

I will be touring some schools and doing some festivals to meet future readers of this extremely educational book in the next few weeks. Full report to follow!

Clem x

Back to the desktop

Hello again, after a rather long break. This summer, I had fake holidays (=conferences) and real holidays (= real holidays). After two months of June and July spent working quite intensely on my monograph (the final revisions of which I submitted at the end of July), I went to the International Bakhtin Conference in Stockholm at the end of July, disguised as a Bakhtin scholar (which I’m not). There, I was the discussant at a panel given by my colleagues Maria Nikolajeva, Eve Tandoi and Faye Dorcas Yung on Bakhtinian approaches to children’s literature.

The highlight of the conference (apart from a textbook example of mansplaining I had to endure from a charming middle-aged professor) was the re-enactment of Mikhail Bakhtin’s doctoral viva, in which Maria played one of the external examiners. All the genders were switched, so Bakhtin himself was played by a young female academic with absolutely spot-on facial expressions of weariness and annoyance at the objections s/he was receiving.

Can you imagine having your PhD viva re-enacted? Yeah, me neither. But then it certainly wouldn’t make such good drama. Despite Maria’s character’s insistence that ‘to refuse Comrade Bakhtin the title of Doctor would be ridiculous’, poor Mikhail only managed to get the equivalent of a Masters’, in part because of the non-political nature of his work. A female comrade from the audience (played by a male British Bakhtin scholar) had indeed bemoaned the shocking lack of references to Marx and to Lenin in the analysis of Rabelais.

Stockholm was staggeringly hot – pretty much 30 to 33 degrees the whole week. I actually fell asleep in an aftenoon talk, which had never happened to me before. But this meant that we got more than the usual side-tourism done – we even swam almost everyday in the beautiful bay, including on the Baltic Sea side which was petrifyingly cold.

I then went on actual holiday. When you’re an academic, talking to other academics, there’s a kind of understanding that if you’re going away somewhere nice, it’s probably for a conference. So if someone tells you, ‘I’m going to Hawaii tomorrow,’ the correct reply is, ‘What’s the conference going to be about?’. Not so in August, when I managed to spend a week in the tiny village in the North of France where we have a small holiday house, and then a full two weeks in Rome.

My Roman holiday wasn’t tourism-only, though, as I’d decided to spend every afternoon working on the first draft of my next French teenage novel, and thankfully managed it. I’d been working on it for over a year, but very on and off – contrary to my English work, in France I don’t get contracts before I write a book, which means no deadlines – so writing them is always very low on my to-do list, even though I enjoy it a lot. This new novel is, contrary to my first two (very grim) YA books, a comedy.

What now awaits me as I’m back in Cambridge is a daunting to-do list, both on the fiction side and on the academic side. I’ve got several ‘Revise and Resubmit’ or ‘Revise with major corrections’ articles to, well, revise and resubmit. I have to do the index for my monograph. I’ve been contracted for two more books in the Royal Babysitters series with Bloomsbury, which I need to write between now and April.

The first book, The Royal Babysitters, is coming out on September 11th and I’m going on a small promotion tour with a number of schools. I’m also doing a few festivals here and there, and going to Lake Leman next week for a big book fair, this time mostly for my French books.

I’m also bracing for what is going to be a heavy year in terms of teaching. I’ve taken on many new lectures, including in the fields I’m now branching into – sociology and philosophy of childhood and education – and I will also be teaching Creative Writing courses (on children’s fiction) at the Institute of Continuing Education in Cambridge. I’ll also keep supervising, though probably not as much as the years before as my teaching load is too big already. I will probably miss it a bit, as I’ve been enjoying supervising undergraduates more and more, and was particularly spoiled last year with some very bright, very motivated students.

I hope you all had a nice summer too, and leave you with what was, to me, the most stupefying thing in Rome – and a reminder not to forget about sensuality and beauty while in the midst of frantic term-time…

Royal Cover!

Hurrah! We’ve got a cover for The Royal Babysitters! and it’s as yellow as royal jelly, and as energetic as the story inside. I’m absolutely thrilled with it – look at that!

All thanks to the great Becka Moor and the Bloomsbury designers…

All thanks to the great Becka Moor and the Bloomsbury designers…

It’s got everything a good cover needs: a prince with ice-cream cones stuck behind his ears, a very large number of royal babies, a robot sea monster, a snake and a zeppelin piloted by a mad king. Therefore, I call it an extremely successful cover.

Since it’s been approximately a very long time since I told you about this series, here’s a reminder of the story:

In another world not quite at all like our own, though very like it in other respects, but mostly not, although a little bit, the King and Queen of Britland are going on their annual day of leave to the Independent Republic of Slough. As a result, they are in urgent need of a royal babysitter for their two three four numerous little princely toddlers. Coincidentally, Anna and Holly Burnbright are in urgent need of two thousand pounds to go on an intergalactic holiday they’ve seen advertised in the newspaper. Great summer job opportunity, no?

Uh oh, it’s also the day King Alaspooryorick of Daneland has chosen to invade Britland…

The Royal Babysitters is out in September and will be followed by The Royal Wedding-Crashers in April, when Anna, Holly and Prince Pepino will be off to Francia.

And yes, I promise, I’ll update this blog soon again. I’ve been revising my monograph. I might talk about that, because it’s so thrilling it’s almost worthy of its own Buzzfeed article.

Clem

Productivi-tips

Last week I wrote a blog post deploring the fact that I couldn’t write slowly. In response, two of my friends suggested I blogged about how to be ‘productive’. I’m a bit ambivalent, since, as hinted in that blog post, ‘productivity’ has a dark side. It can be efficiently generated by the cultivation of guilt, worry about the future and insecurity in children from a young age (I’m looking at you, French educational system), as well as by inordinately high standards.

So my immediate sarcastic response was: Tip number one: set yourself irrationally high goals, self-flagellate every time you don’t work enough to attain them, find people who are much better than you and mull over how superior they are, and for good measure, add the threat of never finding a job. Your productivity will rocket, I promise.

Well, let that be a disclaimer: even though this is a ‘tips’ blog post, there are issues with ‘tips’ about productivity, just like there are issues with ‘tips’ about losing weight, for instance.

But here are a few things that I do find genuinely useful in increasing productivity, that is to say, in my case, getting (preferably good) words on the page, whether academic or fictional, and making sure they get published (i.e. editing, revising, referencing, etc); and doing teaching-related work.

- Switching off the Internet entirely

Just as I’m writing this, a little (1) pops up on my Facebook tab. I have to check what it is, because it could be someone tagging a picture of me drunkly lap-dancing in a bar. Let’s see. No, it’s fine, it’s just someone I friended in 2008 mass-inviting all his Facebook acquaintances to sponsor his half-marathon on a space hopper. I’m never going to sponsor him, but I still read the whole description and end up wikipediaing the charity he’s space-hopping for, which knits socks and scarves for yellow-bellied marmots. I suddenly remember I have a blog post to write, but now a little (1) has appeared on the Outlook tab…

Sorry, what? Oh yes – the Internet. Let’s not write that blog post online – too distracting. Write it in a Word document instead. Internet can stay open behind Word. Oh no it can’t, because some idiot at Microsoft thought it would be an excellent idea to make Word vaguely translucent at the top, which means I can still distinguish the little (1)s through a half-hearted vapour of pixels.

Solution: turn it off altogether with Cold Turkey (SelfControl for Mac users). I couldn’t have written anything in the past two years without Cold Turkey. It didn’t even get a mention in my thesis acknowledgements, because I preferred to pretend that real humans such as my supervisor, friends and family were more responsible for its completion, which is a lie, however much I love them.

Those pieces of software only block the websites you want them to block, which means you can still use JStor and Project Muse, where procrastination opportunities are few (until you start typing up your own name to see what comes up and this does).

Those pieces of software only block the websites you want them to block, which means you can still use JStor and Project Muse, where procrastination opportunities are few (until you start typing up your own name to see what comes up and this does).

- Pomodoroing through multiple projects

I do this when I work on very many projects that are all at different stages of development, because that’s when I’m most at risk of using the exciting ones as excuses to procrastinate on the others. The Pomodoro technique basically states that you should set yourself short spans of time for work, interspersed with breaks. Strictly speaking, it’s supposed to be 20 minutes, but that’s too short to do anything constructive in academic or fiction writing.

I make myself work generally for an hour or an hour and a half on many projects everyday, strictly interrupting the one I’m doing when time’s up (yes, even in the middle of a sentence) to start work on the next one (or take a break).

Breaks can be used to check and reply to email, though it’s much better if you can actually force yourself not do anything at all.

I use the Pomodoro technique only when I’m feeling overwhelmed by the quantity and variety of different projects. It’s also much easier during student holidays, when there aren’t too many meetings, supervisions and essays to mark.

The good thing about this technique is that you never work long enough to get bored of the projects. If anything, it makes you frustrated when you have to stop – which means that the next day, you’re happy to find that piece of work again.

- Taking on more work, or setting earlier deadlines.

I find that productivity augments, rather than declines, when I’ve got more to do. This is, in part because although I can (on good days) focus intensely on writing or research for up to six or seven hours, it’s extremely rare when I can have that focus for one project. Paradoxically, taking on more projects and making sure you’ve always got one or two deadlines soonish makes me achieve more and feel happier.

- Keeping a strict and very subdivided to-do list.

I list everything, even things like ‘reply to X’s email’ if I know it will take me more than 3 minutes to compose. If I have 20 undergrad essays to mark, I’ll list the names of all 20 people and cross them out as I go along. Purely psychological, of course, but those manageable tasks give the impression of being productive, which leads to actually being productive.

I also have 4+ separate to-do lists corresponding to different domains (fiction, admin, research, teaching, etc.), which avoids clutter. My to-do lists are on (virtual) post-it notes on my desktop, like (virtually) everyone else I know.

- Doing either work or leisure activities

Wait but Why says it perfectly: there are two types of good weeks: days when you achieve something that ‘improves your future or that of others’ (even in small ways), and weeks of pleasure, leisure and enjoyment. Both at the same time makes for an ‘ideal’ week, which is rare.

And in-between, there’s a wearisome kind of activity, where you know you’re not actually having any fun, but you’re not doing anything particularly valuable either. This is the case, for instance, if you spend most of a day half-heartedly writing a few sentences, checking email, marking half an essay, checking the news, reading half a paper, checking the weather, etc. It’s tiring and makes you feel gross, while both real work and real leisure makes you invigorated and happy.

- Picking the right times for small projects or admin tasks

It’s tempting to get small tasks or long tasks that don’t take much brainpower out of the way (i.e. filling in forms, doing tax returns etc.). But then you just end up wasting valuable energy, and possibly spending too much time on them out of a semi-conscious desire to procrastinate work on important stuff. Again, I find it useful to time those important but boring activities strictly, and stick them at moments of the day when you know you won’t be very switched-on anyway.

- Using up as much available time as possible.

It’s hard to focus on anything when you know you’ve got to leave in 10 or 20 minutes, but with some tasks it’s entirely possible. I wrote most of this blog post in chunks of 5 or 10 minutes. I have a number of tasks on my to-do list that I know I can do in instalments, quickly dipping in and out when needed.

- Sacrifice some things.

For instance, this blog and my French one. I don’t care (much) if I don’t have the time to deliver the weekly Wednesday post.

I’d be curious to hear what you do to increase productivity, and/or take issue with such blog posts as this one on ideological grounds.